Herschel Walker

Herschel Walker | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

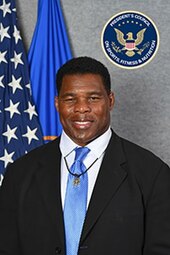

Walker in 2013 | |||||||||||||||

| United States Ambassador to the Bahamas Nominee | |||||||||||||||

| Assuming office TBD | |||||||||||||||

| President | Donald Trump | ||||||||||||||

| Succeeding | Kimberly Furnish (Chargé d'Affaires) | ||||||||||||||

| Co-chair of the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports | |||||||||||||||

| In office 2019–2020 | |||||||||||||||

| President | Donald Trump | ||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Dominique Dawes Drew Brees | ||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Elena Delle Donne José Andrés[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||

| Born | Herschel Junior Walker March 3, 1962 Augusta, Georgia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Political party | Republican | ||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

Cindy DeAngelis Grossman

(m. 1983; div. 2002)Julie Blanchard (m. 2021) | ||||||||||||||

| Children | 4, including Christian | ||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Georgia (BS)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||

| Awards | Full list | ||||||||||||||

|

American football career | |||||||||||||||

| No. 34 | |||||||||||||||

| Position: | Running back | ||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||

| Born: | March 3, 1962 Augusta, Georgia, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight: | 225 lb (102 kg) | ||||||||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||||||||

| High school: | Johnson County (Wrightsville, Georgia) | ||||||||||||||

| College: | Georgia (1980–1982) | ||||||||||||||

| NFL draft: | 1985 / round: 5 / pick: 114 | ||||||||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Martial arts career | |||||||||||||||

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm) | ||||||||||||||

| Weight | 220 lb (100 kg; 15 st 10 lb) | ||||||||||||||

| Division | Heavyweight | ||||||||||||||

| Reach | 76 in (193 cm) | ||||||||||||||

| Stance | Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Fighting out of | San Jose, California, U.S. | ||||||||||||||

| Team | American Kickboxing Academy | ||||||||||||||

| Trainer | Bob Cook | ||||||||||||||

| Rank | 5th degree black belt in Taekwondo[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Mixed martial arts record | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Wins | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| By knockout | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||

| Mixed martial arts record from Sherdog | |||||||||||||||

Herschel Junior Walker (born March 3, 1962) is an American politician and former professional football running back who won the Heisman Trophy and Maxwell Award in 1982 and later played 15 years of football in the United States Football League (USFL) and National Football League (NFL). Off the field, he was the Republican nominee in the 2022 United States Senate election in Georgia, and is the nominee for United States Ambassador to the Bahamas in President Donald Trump's second term.[4]

Walker played college football at the University of Georgia, winning the Heisman Trophy and Maxwell Award as a junior.[5] He spent the first three seasons of his professional career with the New Jersey Generals of the USFL and was the league's MVP during its final season in 1985. After the USFL folded, Walker joined the NFL with the Dallas Cowboys, earning consecutive Pro Bowl and second-team All-Pro honors from 1987 to 1988. In 1989, Walker was traded to the Minnesota Vikings, which is regarded as one of the most lopsided trades in NFL history and credited with establishing the Cowboys' dynasty of the 1990s. He was later a member of the Philadelphia Eagles and New York Giants before retiring with the Cowboys. Walker was inducted to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1999.

Outside of football, Walker was a member of the United States' bobsleigh team at the 1992 Winter Olympics and pursued business ventures in food processing. From 2019 to 2020, he served as a co-chair on the President's Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition under President Donald Trump. Walker launched his first political campaign in Georgia's 2022 Senate election, which he lost to Democratic incumbent Raphael Warnock.[6]

On December 18, 2024, President-elect Trump announced that he had selected Walker as his nominee to serve as U.S. Ambassador to the Bahamas.[7]

Early life and education

[edit]Walker was born in Augusta, Georgia, to Willis and Christine Walker. He was raised in Wrightsville, Georgia.[8] He was one of seven children. Walker said that as a child, he was overweight and had a stutter.[9][10]

Walker attended Johnson County High School in Wrightsville, where he played football, basketball, and competed in track. He played for the Johnson County Trojans high school football team from 1976 to 1979. In his senior year, he rushed for 3,167 yards, helping the Trojans win their first state championship.[11] He was awarded the inaugural Dial Award as 1979 national high school scholar-athlete of the year.[12]

Walker also competed on the Trojans track and field team in events ranging from the 100-yard dash to the shot put.[13] He won the shot put, 100-yard dash, and 220-yard dash events at the Georgia High School Association T&F State Championships. He also anchored the 4×400 team to victory. [citation needed]

In his 2008 autobiography, Walker wrote that he was the Beta Club president and class valedictorian at Johnson County High School.[14] In December 2021, Walker's Senate campaign website claimed he graduated as the valedictorian of the entire high school, but CNN found no evidence for this claim.[14] The claim on Walker's website was later removed and amended to state that Walker graduated high school "top of his class".[14]

Starting in 2017, Walker has made the false claim that he had graduated from University of Georgia "in the top 1% of his class".[14] In fact, he did not graduate, and left college to join the USFL.[15] He had yet to return to complete his degree.[16][14] In December 2021, Walker's Senate campaign website deleted the assertions about his education after The Atlanta Journal-Constitution inquired about it, with Walker acknowledging in a statement that he left the university prior to graduation to play professional football.[17] Walker later falsely asserted he never said he graduated from the university.[16] 42 years after his initial enrollment, he graduated from the institution with a Bachelor of Science in Family and Consumer Sciences degree in Housing Management and Policy on December 16, 2024.[18]

Walker played running back and ran on the track and field team for the University of Georgia, where he was a three-time unanimous All-American (football and track), and winner of the 1982 Heisman Trophy and Maxwell Award.[19] He is the first NCAA player who played only three years to finish in the top 10 in rushing yards, a mark later tied by Jonathan Taylor.[citation needed] During his freshman season in 1980, Walker set the NCAA freshman rushing record which was later broken by Taylor. Walker finished third in Heisman voting. Walker was the first "true freshman" to become a first-team All-American.[20] As a freshman, he played a major role in helping Georgia go undefeated and win the de facto national championship with a victory over Notre Dame in the Sugar Bowl. In 1999, Walker was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame.[19]

College statistics

[edit]| Season | Team | Rushing | Receiving | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Att | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Rec | Yds | TD | ||||

| 1980 | Georgia | 274 | 1,616 | 5.9 | 76 | 15 | 7 | 70 | 1 | ||

| 1981 | Georgia | 385 | 1,891 | 4.9 | 32 | 18 | 14 | 84 | 2 | ||

| 1982 | Georgia | 335 | 1,752 | 5.2 | 59 | 16 | 5 | 89 | 1 | ||

| Career | 994 | 5,259 | 5.3 | 76 | 49 | 26 | 243 | 4 | |||

Professional career

[edit]United States Football League

[edit]Walker signed with the New Jersey Generals in 1983, owned by Oklahoma oil tycoon J. Walter Duncan, who after the 1983 season sold the team to Donald Trump.[21] Walker attracted only one major promotional offer, a joint project of McDonald's and Adidas.

National Football League

[edit]Dallas Cowboys (first stint)

[edit]The Dallas Cowboys, aware of Walker's earlier interest in playing for them, acquired Walker's NFL rights by selecting him in the fifth round (114th overall) of the 1985 NFL draft.[22]

In 1986, he was signed by the Cowboys and moved to fullback, so he could share backfield duties with Tony Dorsett, becoming the second Heisman backfield tandem in NFL history, after George Rogers and Earl Campbell teamed with the 1984 New Orleans Saints. This move created tension, as it would limit Dorsett's playing time, and because Walker's $5 million five-year contract exceeded his $4.5 million five-year contract.[citation needed] Walker rushed for the game-winning touchdown with a minute to play in the 31–28 victory against the New York Giants in the season opener. In the week 15 game against the Philadelphia Eagles, he had a franchise-record 292 yards of total offense, including the NFL's longest run of the year with an 84-yarder for a touchdown and an 84-yard touchdown reception.[23]

In 1987, Walker complained to Cowboys management about being moved around between three different positions (running back, fullback, wide receiver) and that Dorsett had more carries. He would be the team's main running back, playing in 12 games (11 starts), while registering 891 rushing yards, 715 receiving yards, and 8 touchdowns. Dorsett played in 12 games (6 starts) and had two healthy DNP (Did Not Play), which would make him demand a trade that would send him to the Denver Broncos.[24]

Walker established himself as an NFL running back in 1988, becoming a one-man offense, reaching his NFL career highs of 1,514 rushing yards and 505 receiving yards, while playing seven positions: halfback, fullback, tight end, H-back, wide receiver, both in the slot and as a flanker.[25] He became the 10th player in NFL history to amass more than 2,000 combined rushing and receiving yards in a season. In the process he achieved two consecutive Pro Bowls (1987 and 1988).[26][27]

In 1989, the Cowboys traded Walker to the Minnesota Vikings for a total of five players (linebacker Jesse Solomon, defensive back Issiac Holt, running back Darrin Nelson, linebacker David Howard, defensive end Alex Stewart) and six future draft picks. The five players were tied to potential draft picks Minnesota would give Dallas if a player was cut (which led to Emmitt Smith, Russell Maryland, Kevin Smith, and Darren Woodson).

Minnesota Vikings

[edit]Walker's trade to Minnesota was initially considered by many as supplying the Vikings with the "missing piece" for a Super Bowl run; however, over time, as the Cowboys' fortunes soared and the Vikings' waned, it became viewed as, perhaps, the most lopsided trade in NFL history.[28][29][30] From the moment he arrived in Minneapolis, "Herschel Mania" erupted. After a 2½ hour practice where he studied 12 offensive plays, Walker debuted against the Green Bay Packers.

He received three standing ovations from the record Metrodome crowd of 62,075, producing a Vikings win after four successive losses and 14 of the prior 18 games with the Packers. Scout.com says, "Walker was never used properly by the coaching brain trust."[31] However, the Vikings would not make the playoffs, let alone the Super Bowl, in Walker's two full seasons there.

"Herschel the Turkey", a mock honor given out by the Star Tribune newspaper to inept Minnesota sports personalities, is named for him.[32]

Philadelphia Eagles

[edit]After three seasons in Minnesota, the Philadelphia Eagles signed Walker in 1992 hoping he would help them reach the Super Bowl.[33] That year, he rushed 267 times for 1,070 rushing yards and eight rushing touchdowns to go along with 38 receptions for 278 receiving yards and two receiving touchdowns as the Eagles advanced to the Divisional Round before being eliminated.[34][35]

In the 1993 season, Walker rushed 174 times for 746 rushing yards and one rushing touchdown. He was a significant part of the receiving game for the 8–8 Eagles with 75 receptions for 610 receiving yards and three receiving touchdowns.[36][37]

In 1994 he became the first NFL player to have one-play gains of 90 or more yards rushing, receiving and kick-returning in a single season. He spent three seasons in Philadelphia, leaving after the Eagles signed free agent Ricky Watters.

New York Giants

[edit]The New York Giants signed Walker in 1995 to a three-year contract worth $4.8 million[38] as a third-down back. Walker led the Giants with 45 kick returns at 21.5 yards per return in 1995, his only season with the team.[39]

Dallas Cowboys (second stint)

[edit]In 1996, he rejoined the Dallas Cowboys as a kickoff return specialist and third-down back. He also played fullback, but primarily as a ball-handler instead of a blocker out of I-Form and pro-sets. Walker retired at the end of the 1997 season.

Professional statistics

[edit]USFL

[edit]| USFL career stats | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Jersey Generals | ||||||||||||||||

| Year | Rushing | Receiving | Kick returns | 2Pt | ||||||||||||

| Att | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Rec | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Ret | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | ||

| 1983 | 412 | 1,812 | 4.4 | 80 | 17 | 53 | 489 | 9.2 | 65 | 1 | 3 | 69 | 23.0 | 27 | 0 | 1 |

| 1984 | 293 | 1,339 | 4.6 | 69 | 16 | 40 | 528 | 13.2 | 50 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1985 | 438 | 2,411 | 5.5 | 88 | 21 | 37 | 467 | 12.6 | 68 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Career | 1,143 | 5,562 | 4.9 | 88 | 54 | 130 | 1,484 | 11.4 | 68 | 7 | 3 | 69 | 23.0 | 27 | 0 | 2 |

NFL

[edit]| NFL career stats | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Team | GP | Rushing | Receiving | Kick returns | ||||||||||||

| Att | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Rec | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | Ret | Yds | Avg | Lng | TD | |||

| 1986 | DAL | 16 | 151 | 737 | 4.9 | 84 | 12 | 76 | 837 | 11.0 | 84 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1987 | DAL | 12 | 209 | 891 | 4.3 | 60 | 7 | 60 | 715 | 11.9 | 44 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1988 | DAL | 16 | 361 | 1,514 | 4.2 | 38 | 5 | 53 | 505 | 9.5 | 50 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1989 | DAL | 5 | 81 | 246 | 3.0 | 20 | 2 | 22 | 261 | 11.9 | 52 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 |

| MIN | 11 | 169 | 669 | 4.0 | 47 | 5 | 18 | 162 | 9.0 | 24 | 2 | 13 | 374 | 28.8 | 93 | 1 | |

| 1990 | MIN | 16 | 184 | 770 | 4.2 | 58 | 5 | 35 | 315 | 9.0 | 52 | 4 | 44 | 966 | 22.0 | 64 | 0 |

| 1991 | MIN | 15 | 198 | 825 | 4.2 | 71 | 10 | 33 | 204 | 6.1 | 32 | 0 | 5 | 83 | 16.6 | 21 | 0 |

| 1992 | PHI | 16 | 267 | 1,070 | 4.0 | 38 | 8 | 38 | 278 | 7.3 | 19 | 2 | 3 | 69 | 23.0 | 34 | 0 |

| 1993 | PHI | 16 | 174 | 746 | 4.3 | 35 | 1 | 75 | 610 | 8.1 | 41 | 3 | 11 | 184 | 16.7 | 30 | 0 |

| 1994 | PHI | 16 | 113 | 528 | 4.7 | 91 | 5 | 50 | 500 | 10.0 | 55 | 2 | 21 | 581 | 27.7 | 94 | 1 |

| 1995 | NYG | 16 | 31 | 126 | 4.1 | 36 | 0 | 31 | 234 | 7.5 | 93 | 1 | 41 | 881 | 21.5 | 67 | 0 |

| 1996 | DAL | 16 | 10 | 83 | 8.3 | 39 | 1 | 7 | 89 | 12.7 | 34 | 0 | 27 | 779 | 28.9 | 67 | 0 |

| 1997 | DAL | 16 | 6 | 20 | 3.3 | 11 | 0 | 14 | 149 | 10.6 | 64 | 2 | 50 | 1,167 | 23.3 | 49 | 0 |

| Career | 187 | 1,954 | 8,225 | 4.2 | 91 | 61 | 512 | 4,859 | 9.5 | 93 | 21 | 215 | 5,084 | 23.6 | 94 | 2 | |

Other athletic and competitive activities

[edit]In 1992, Walker competed in the Winter Olympics in Albertville, France as a member of the United States' bobsleigh team. Originally selected for the four-man team, he eventually competed as the brakeman (or pusher) in the two-man competition.[40][41] Walker and his teammate Brian Shimer placed seventh.

In November 2007, Walker appeared on the HDNet show Inside MMA as a guest. He indicated he would take part in a mixed martial arts reality show in the near future (along with José Canseco) and that he would have an official MMA fight at the conclusion of the show.[42] In September 2009, it was announced that Walker had been signed by MMA promotion company Strikeforce to compete in their heavyweight division at the age of 47.[43]

He began a 12-week training camp with trainer "Crazy" Bob Cook at the American Kickboxing Academy in October 2009 in San Jose, California.[44] In his MMA debut on January 30, 2010, Walker defeated Greg Nagy via technical knock-out due to strikes at Strikeforce: Miami.[45][46]

In 2009, Walker was a contestant in the second season of the reality television show The Celebrity Apprentice.

Strikeforce confirmed that Walker would face former WEC fighter Scott Carson when he made his second appearance in the Strikeforce cage.[47] Walker was forced off the Strikeforce card on December 4 due to a cut suffered in training that required seven stitches. They fought instead on January 29, 2011, and Walker defeated Carson via TKO (strikes) at 3:13 of round 1.[48]

In 2014, Walker won season 3 of Rachael vs. Guy: Celebrity Cook-Off.

Walker has a fifth-degree black belt in taekwondo.[3]

Mixed martial arts record

[edit]| 2 matches | 2 wins | 0 losses |

| By knockout | 2 | 0 |

| Res. | Record | Opponent | Method | Event | Date | Round | Time | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 2–0 | Scott Carson | TKO (strikes) | Strikeforce: Diaz vs. Cyborg | January 29, 2011 | 1 | 3:13 | San Jose, California United States | |

| Win | 1-0 | Greg Nagy | TKO (punches) | Strikeforce: Miami | January 30, 2010 | 3 | 2:17 | Sunrise, Florida, United States | Heavyweight debut. |

Business activities

[edit]In 1984, Walker franchised a D'Lites fast food restaurant in Athens, Georgia.[49]

In 2002, Walker created Renaissance Man Food Services, which distributes chicken products.[50] Originally, his producer was Sysco Corp. following a casual conversation with a Sysco vice president who asked him to provide some chicken-breading recipes from his mother.[51] He founded Savannah-based H. Walker Enterprises in 2002 as an umbrella company for most of his other business ventures, the largest of which was Renaissance Man Food Services.[52]

Walker has a history of exaggerating the number of people employed by and the assets of his companies; the failure of several business enterprises led to creditors bringing lawsuits.[52][53] Walker touted Renaissance Man Food Services as one of the largest minority-owned meat processors in the nation, with $70 million in annual sales.[52][51] In subsequent deposition testimony in a lawsuit, however, Walker gave far lower figures, saying that his company averaged about $1.5 million in annual profits from 2008 and 2017.[53]

Walker has touted Renaissance Man Food Services as a "mini-Tyson Foods", and also said that the company controlled multiple chicken processing plants.[52][54] However, in a 2018 declaration submitted in a legal case against his company, Walker acknowledged that the company did not actually own any chicken processing plants and instead partnered with plant owners to sell branded chicken products.[52] Walker's business associates later testified that Walker licensed his name to the chicken-related enterprise.[53]

In 2009, Walker told the media that Renaissance Man Food Services had over 100 employees.[52] In 2018, Walker told the media that Renaissance Man Food Services had "over 600 employees."[52][55] In 2020, Renaissance Man Food Services informed the U.S. government that it had eight employees.[52][53] The Atlanta Journal-Constitution suggested that Walker's overestimate of employees could "refer to chicken processing jobs, which are not actually part of Walker's business".[52]

In April 2020, Renaissance Man Food Services applied for a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic,[56] and the company ultimately received two PPP loans totaling $180,000 (of which $111,300 was forgiven).[52] On Twitter in April 2020, Walker mocked "big companies" that received PPP money, suggesting that they were "giving back" the money due to being "ashamed".[57] This was despite Walker being a board member of the Sotherly Hotel Group, owner of the Georgian Terrace Hotel and other hotels; the group received over $9 million of PPP loans in April 2020 while firing 90% of its hotel staff, according to company documents submitted to the U.S. government.[57] According to government records, Walker was paid $247,227 in total from Sotherly from 2016 to 2021.[57]

Walker said that "part of its corporate charter" was to donate 15% of profits to charities. However, none of the four charities that Walker named as beneficiaries confirmed they actually received any donations.[58]

Political activities

[edit]

In 2014, Walker appeared in a commercial paid for by the United States Chamber of Commerce supporting Jack Kingston's bid in the Republican primary election for the 2014 U.S. Senate election in Georgia.[59] In 2018, Walker endorsed Republican Brian Kemp in the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial election.[60]

Walker supported Donald Trump in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections,[61] and spoke on Trump's behalf at the 2020 Republican National Convention.[62] In 2018, Trump appointed Walker to the President's Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition.[63] Trump reappointed him to another two year-term on December 17, 2020.[64] He was removed from the position in March 2022 by President Biden after he was asked to resign.[65] In 2020, Walker endorsed U.S. Senator Kelly Loeffler.[66]

2022 U.S. Senate election in Georgia

[edit]In 2021, Donald Trump encouraged Walker to run for the U.S. Senate in Georgia.[67] Walker, a Texas resident, needed to re-establish residency in Georgia to do so.[68] Walker's contemplation of entering the race "froze" the Republican field because other prospective candidates for the nomination waited for his decision.[69][67] In July 2021, Fox News reported that some Georgia Republicans were not sure how effective a candidate Walker would be, citing the fact that his positions on issues of importance to Republican voters were unknown.[70]

In August 2021, Walker announced his run for the Senate seat held by Democrat Raphael Warnock.[68] Walker began his campaign with high favorability ratings and support from self-identified moderate Republicans, and, in October 2021, was endorsed by Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, in a sign that the Republican establishment was lining up behind him.[71][72]

In June 2022, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found Walker's claims about working in law enforcement were either false or unverifiable.[73] Walker has been named as an honorary deputy sheriff in Cobb County and Johnson County.[74] In 2019, Walker said he "spent time at Quantico at the FBI training school" and was "an agent" when, in reality, Walker lacked the bachelor's degree required for FBI training.[73] Previously, in 1989, Walker told the media that he "had fun" while attending an FBI school in Quantico for a week, speaking of an "obstacle course and you shoot at targets".[73]

Many of Walker's statements on the campaign trail have been described as "gaffes"[75] or "head-scratching at best".[76] In an editorial for CNN, Chris Cillizza described Walker as a "walking gaffe machine", and disputed several statements Walker had made.[77]

On October 5, 2022, Walker's campaign fired Taylor Crowe, his campaign political director, over suspicions that he leaked information to the media.[78]

On October 14, 2022, Walker and his Democratic challenger, Raphael Warnock, faced off in their only debate for the Senate election.[79] The New York Times described Walker's demeanor throughout the debate as "aggressive and persistent," with his frequent interruptions of Warnock and mocking of him for dodging questions.[80] Walker repeatedly tried to link Warnock with President Joe Biden, who carried a low approval rating.[81][82] During a portion of the debate focusing on crime, Walker revealed what appeared to be a law enforcement badge[a] to illustrate his closeness to law enforcement; he was admonished by the moderators since props were not allowed during the debate.[84] The Hill wrote Walker won a "moral victory by avoiding disaster" and "more than avoided embarrassment."[85]

In a mid-November 2022 campaign speech, Walker discussed watching a film about a vampire, whom he compared to Warnock with a "black suit". The film showed a person failing to defeat the vampire, said Walker, because of a lack of "faith". Walker made a call to "have faith in our fellow brothers ... have faith in the elected officials ... that's the reason I'm here ... I'm that warrior that y'all have been looking for". Also during that speech, Walker said: "A werewolf can kill a vampire ... So, I don't want to be a vampire any more. I want to be a werewolf."[86][87][88]

Since no candidate received a majority of the vote in the general election on November 8, 2022, he faced incumbent Democrat Raphael Warnock in a runoff election on December 6, and lost. The final tally of votes was 51.40% for Warnock and 48.60% for Walker.[89][90] Walker conceded the election that night, stating: "I'm not going to make any excuses now because we put up one heck of a fight. [...] I want you to continue to believe in this country, believe in our elected officials, and most of all, stay together".[91]

Political positions

[edit]2020 presidential election

[edit]After Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election, Walker tweeted a video supporting Trump's efforts to overturn the election results.[67] Walker has spread many conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election.[92][93] Walker claimed that Biden "didn't get 50 million" votes; Biden indeed received over 80 million votes.[92] Walker alleged that there was "country-wide election fraud" and urged Trump and "true patriots" to carry out "a total cleansing" to "prosecute all the bad actors".[92] He urged re-votes in the states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.[92] Walker also spread a conspiracy theory about the 2021 United States Capitol attack, suggesting it was a "well-planned" distraction from election fraud.

In July 2022, when asked whether Joe Biden had fairly defeated Donald Trump in Georgia, Walker replied, "I have no clue."[94] In the October debate with Warnock, when asked if Joe Biden was the winner of the 2020 election, Walker stated, "President Biden won and Raphael Warnock won."[95]

Abortion

[edit]In May 2022, Walker stated he opposes abortion, and wants no exceptions to abortion bans. He also called for more money to promote adoption and to support single parents. "You never know what a child is going to become. And I've seen some people, they've had some tough times, but I always said, 'No matter what, tough times make tough people.'"[96][97] When asked about the impact of the issue on the November 2022 election, Walker described abortion rights as among the "things that people are not concerned about".[98] In September 2022, Walker endorsed legislation proposed by Senator Lindsey Graham that would ban abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy nationwide, except in cases of rape, incest, and threat to the life of the patient.[99] During his October debate with Raphael Warnock, Walker softened his position on abortion,[100] saying he supported the Georgia law allowing exceptions for rape and threats to the mother's life and health.[101]

On October 3, 2022, The Daily Beast published allegations from a woman who said that Walker impregnated her and paid for her abortion in 2009 when they were dating.[102] The woman supported the allegation by producing images of a personal check from Walker, a get-well card with Walker's purported signature, and a $575 receipt for an abortion.[102][103] The Daily Beast said that it corroborated the story with a friend of the woman, who "took care of her in the days after the procedure".[104] Walker stated, "I never asked anyone to get an abortion. I never paid for an abortion." When asked about the check, Walker said, "I give money to people all the time, because I'm always helping people".[104] Walker said he would sue The Daily Beast for defamation.[105][106] After Walker said on October 5 that he did not know the identity of the woman accusing him, The Daily Beast reported that the woman is the mother of one of Walker's children; she told The Daily Beast that she had another child with Walker years after the abortion, despite Walker stating that it was not a convenient time for him to have a child, a sentiment he also raised prior to the abortion.[107][108]

Within a week of the original allegations' publication, The New York Times interviewed the same woman, as well as her friend, corroborating the reporting by The Daily Beast.[109] The woman additionally told The New York Times that she ended her relationship with Walker when he advised her to have a second abortion in 2011.[109] Family court records in New York confirm that Walker and the woman had a son, who was born in 2012.[109] On October 7, 2022, Walker acknowledged that his accuser was the mother of his son, and as to whether she had an abortion, Walker said: "I'm not saying she did or didn't have one [an abortion]. I'm saying I don't know anything about that." He acknowledged the possibility of having given his accuser a 'get well' card and a check for other reasons, but said he could not remember doing so.[110]

In an October 26, 2022, press conference organized by attorney Gloria Allred, a second woman, who has not identified herself, alleged she had been pressured by Walker to get an abortion in 1993 after a years-long extramarital relationship with him.[111][112] Walker denied the allegation, saying it was a "lie".[111] On November 22, Allred held another press conference, where the second woman also spoke, and audio recordings of Walker were shared.[113] The woman read out letters that she said Walker wrote, including one to her which stated: "I'm sorry I have put you through all this stuff."[113] Allred read out a signed declaration of a friend of the second woman, which stated that the second woman originally said that she had a miscarriage, but the friend suspected that it was an abortion because the friend knew that Walker was married at the time and did not want to have a child with the second woman; years later, the second woman told the friend that Walker actually sent her to a clinic for an abortion.[113]

Economy

[edit]Walker favors reducing federal regulations to boost business. He supports widespread tax cuts, building the Keystone Pipeline and increasing production of fossil fuels. He proposes to "lower healthcare costs by increasing competitive market options".[114] Walker supports putting closed oil fields back into production and rolling back oil-field regulations in order to reduce inflation.[94]

Environment and climate change

[edit]When asked about the Green New Deal environmental program, Walker said that he opposed it because "Since we don't control the air our good air decided to float over to China's bad air so when China gets our good air, their bad air got to move. So it moves over to our good air space. Then now we got we to clean that back up."[75] In August 2022, in response to questions about the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which includes funding to counteract climate change, Walker said, "They continue to try to fool you that they are helping you out. But they're not". Possibly referring to a provision that allocated $1.5 billion to the U.S. Forest Service's Urban and Community Forestry Program, Walker added, "Because a lot of money, it's going to trees. Don't we have enough trees around here?"[115] Walker told supporters at a November 2022 rally that America isn't "ready for the green agenda. ... What we need to do is keep having those gas-guzzling cars. We got the good emissions under those cars".[116]

Guns

[edit]When asked in May 2022 on how to tackle gun violence, Walker said: "Cain killed Abel and that's a problem that we have. What we need to do is look into how we can stop those things."[117] Walker then suggested "getting a department that can look at young men that's looking at women, that's looking at their social media", and also by "putting money into the mental health field ... rather than departments that want to take away your rights."[117] When asked if he supported new gun laws in the wake of the Uvalde school shooting, Walker responded: "What I like to do is see it and everything and stuff."[118]

LGBT rights

[edit]Walker opposes allowing transgender athletes to compete in women's sports events, stating in September 2022: "Let's get men out of women's sports".[119] Walker also discussed transgender children in general, stating, "they're telling the young kids in school, you can be a boy tomorrow even if you're a girl... But I want the young kids to know you go to heaven. Jesus may not recognize you. Because he made you a boy. He made you a girl."[119]

Asked about same-sex marriage, Walker said states should be free to decide the legality of same-sex marriage.[120]

National security

[edit]Walker supports a wall at the border with Mexico. He wants the United States to "heavily invest" in the military.[114]

Diplomatic career

[edit]On December 17, 2024, Walker was named by President-elect Donald Trump as his presumptive nominee for the position of U.S. Ambassador to the Bahamas.[121]

Personal life

[edit]Walker has lived in Westlake, Texas,[122] and in the Las Colinas area of Irving, Texas.[123]

In August 2021, as he was preparing to run for U.S. Senate, Walker registered to vote in Georgia and listed his residence as Buckhead, Georgia; the property is owned by his wife Julie Blanchard.[124] However, in a January 2022 political campaign event, Walker said: "I live in Texas … I was sitting in my home in Texas …"[125] Tax records also show that Walker's primary residence for 2021 and 2022 is still registered as Tarrant County, Texas, where he continues to receive property tax breaks.[126][127]

Relationships and children

[edit]Walker married Cindy DeAngelis Grossman, whom he met in college, in 1983. They have a son, Christian, a social media influencer[128][129] After 19 years of marriage, Walker and Grossman divorced in 2002.[130] Julie Blanchard in 2012 said that she was Walker's fiancée; Walker married Blanchard in 2021.[131]

Walker has two additional sons and a daughter whom he did not publicly acknowledge before his 2022 US Senate campaign; he did so in June 2022, one day after The Daily Beast reported on one of his additional sons.[132] Walker said that month, during a conference, that he "never denied" having four children.[133] The Daily Beast later reported that Walker had lied to his 2022 Senate campaign about how many children he had, while The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported "allies to Walker" stating that Walker had not been honest about how many children he had.[134][135] Walker said that he did not publicly acknowledge his children to prevent exposing them to unwanted attention, and criticized the claim that "I hide my children because I don't discuss them with reporters to win a campaign". Earlier during his Senate campaigning, Walker repeatedly discussed his relationship with eldest son Christian.[132][136]

Prior to publicly acknowledging his other children, in a 2020 interview, Walker said that fatherless households were a "major, major problem" in African-American communities.[132] In October 2022, Walker's adult son Christian criticized Walker, stating, "my favorite issue to talk about is father absence. Surprise! Because it affected me. ... He has four kids, four different women. Wasn't in the house raising one of them. He was out having sex with other women."[137][138][139] Also in October 2022, the mother of another of Walker's sons (born in 2012), said that Walker had seen his son "maybe ... three times", with Walker's parenting contributions mostly being court-ordered child support and sporadic gifts, while suggesting that the gifts were actually from Walker's fiancée/wife Julie Blanchard, and not from him.[109]

Domestic violence allegations

[edit]In September 2001, when Walker and Grossman were estranged, an Irving, Texas, police report stated that police were called to Grossman's home by Walker's therapist due to Walker's visit there; Walker was "volatile", had a weapon, and was scaring Grossman.[140] The report stated that Walker "talked about having a shoot-out with police"; the therapist, Jerry Mungadze, defused the situation after speaking to Walker for at least half an hour. The report stated that police confiscated a SIG Sauer handgun from Walker's car, put his home on a "caution list" due to Walker's "violent tendencies", but did not arrest or charge Walker.[140] In a separate incident, Mungadze told the media that when he conducted a therapy session with Walker and Grossman, he called 911 because Walker "threatened to kill" all three of them, prompting the police to arrive; the result of the incident was Walker hitting a door, breaking his fist.[140]

In filing for divorce in December 2001, Grossman accused him of "physically abusive and extremely threatening behavior." After the divorce, she told the media that, during their marriage, Walker pointed a pistol at her head and said: "I'm going to blow your f'ing brains out."[53][140] She also said he had used knives to threaten her.[141] In 2005, a restraining order was imposed on Walker regarding Grossman, after Grossman's sister stated in an affidavit that Walker told her "unequivocally that he was going to shoot my sister Cindy and her [new] boyfriend in the head."[53] As a result, a temporary gun-owning ban was also issued to Walker by a judge.[53] Walker stated that he does not remember the assault or the threats and attributed his aberrant behavior with his wife and others to his dissociative identity disorder for which he was diagnosed in 2001.[141][53]

In January 2012, a woman, Myka Dean, made a report to Irving, Texas, police that when she attempted to end a 20-year "on-off" relationship with Walker, he "lost it" and threatened to wait at her home to "blow her head off".[140] The responding police officer described this as "extreme threats".[140] Federal records show that Dean, as well as her mother and stepfather, were business partners of Walker's, for his company Renaissance Man Inc.[140] Dean died in 2019; Walker's 2022 political campaign stated that the allegations in the 2012 police report were false, and that Walker still had a good relationship with Dean's parents.[140]

In October 2022, Walker's adult son Christian publicly accused Walker of having threatened to kill him and his mother.[142] He addressed Walker on Twitter, stating: "You're not a 'family man' when you left us to bang a bunch of women, threatened to kill us, and had us move over 6 times in 6 months running from your violence ... how DARE YOU LIE and act as though you're some 'moral, Christian, upright man' ... You've lived a life of DESTROYING other peoples lives."[143][144][104] Soon after Christian made the allegations, Walker wrote on Twitter that he loved his son "no matter what".[143]

In December 2022, The Daily Beast reported that Cheryl Parsa, an ex-girlfriend of Walker who lives in Dallas, had alleged that in 2005, during their relationship, she found Walker with another woman. According to Parsa, Walker got angry, put his hands on Parsa's neck and chest, and swung a fist at her.[145][146]

Mental health

[edit]

Walker has spoken publicly about being diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder and has served as spokesperson for a mental health treatment program for veterans.[147] Walker says he wrote the 2008 book Breaking Free: My Life with Dissociative Identity Disorder[148] to help dispel myths about mental illness and to help others.[149] DID is among the most controversial of the dissociative disorders and among the most controversial disorders found in the DSM-5-TR, with many psychiatrists expressing doubts of its validity.[150][151][152]

In the book, Walker wrote that he had a dozen distinct identities, or alters.[53] According to Walker, some of his alters did many good things, but other alters exhibited extreme and violent behavior, which Walker said he mostly could not remember.[141] A competitive alter caused him to play Russian roulette in 1991, as he saw "mortality as the ultimate challenge", he wrote.[53][141] He was formally diagnosed with the disorder in 2001, after he sought professional help for being tempted to murder a man who was late in delivering a car to him.[53]

Walker attributed his divorce to his behavior caused by the disorder.[141] According to Walker's ex-wife, for the first 16 years of their marriage, Walker's alters were somehow controlled, and she had no idea that he had any disorder.[141] Grossman said that the situation greatly deteriorated once Walker was diagnosed, after which he began to exhibit either "very sweet" alters or "very violent" alters who looked "evil".[141] She said that in one situation where Walker exhibited two alters, she was in bed when he held a straight razor to her throat and repeatedly stated that he would kill her.[141] Walker did not deny Grossman's account, saying that he did not remember it, because blackouts were a symptom of the disorder.[141]

While receiving treatment for dissociative identity disorder in May 2002, Walker was the subject of an Irving, Texas, police report made by a friend of Grossman, Walker's ex-wife.[140][153] She said that he followed her home and that she was "very frightened" of Walker, but did not want police to make contact with him as it would "only make the problem worse."[140][153] She reported previously having a "confrontation" with Walker sometime around 2001, which was followed by Walker calling her to threaten her and "having her house watched".[140][153]

Awards and honors

[edit]On July 4, 2017, during Wrightsville's annual Fourth of July celebration and parade, Trojan Way, the street where Johnson County High School resides, was officially renamed Herschel Walker Drive.[154]

In the 1980s, the American Academy of Achievement awarded Walker their Golden Plate Award for being an All-American Football Player.[155][156]

NFL

- Two-time Pro Bowl selection

USFL

- 1985 USFL MVP

NCAA

- 1980 National champion

- 1982 Heisman Trophy winner

- 1982 UPI College Football Player of the Year

- Three-time Unanimous All-American

- Georgia Bulldogs No. 34 retired

- College Football Hall of Fame (class of 1999)

Electoral history

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Herschel Walker | 803,560 | 68.18% | |

| Republican | Gary Black | 157,370 | 13.35% | |

| Republican | Latham Saddler | 104,471 | 8.86% | |

| Republican | Josh Clark | 46,693 | 3.96% | |

| Republican | Kelvin King | 37,930 | 3.22% | |

| Republican | Jonathan McColumn | 28,601 | 2.43% | |

| Total votes | 1,178,625 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock (incumbent) | 1,946,117 | 49.44% | +1.05% | |

| Republican | Herschel Walker | 1,908,442 | 48.49% | −0.88% | |

| Libertarian | Chase Oliver | 81,365 | 2.07% | +1.35% | |

| Total votes | 3,935,924 | 100.0% | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Raphael Warnock (incumbent) | 1,820,633 | 51.40% | +0.36% | |

| Republican | Herschel Walker | 1,721,244 | 48.60% | −0.36% | |

| Total votes | 3,541,877 | 100.0% | |||

| Democratic hold | |||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to a spokesperson from Walker's campaign, the badge was an honorary badge from the Cobb County Sheriff Department that Walker received for community service. However, The New York Times also notes the badge Walker presented on the debate stage was not an authentic badge that trained sheriffs carry, but was rather "an honorary badge often given to celebrities in sports or entertainment."[83]

References

[edit]- ^ https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/presidents-council

- ^ "Georgia football legend Herschel Walker graduates from UGA". December 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "Herschel Walker starts new career in mixed martial arts". masslive. September 22, 2009. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Trump's Cabinet and Key Jobs: Katherine MacGregor, Steven Bradbury Among Latest Staff Picks". Forbes.

- ^ "1982 Heisman Trophy". Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Stahl, Chelsea (December 7, 2022). "Democratic Sen. Warnock defeats Republican Walker in Georgia runoff". NBC News. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Megerian, Chris (December 17, 2024). "Former RB Herschel Walker picked as Bahamas ambassador". Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 24, 2024. Retrieved December 23, 2024.

- ^ Walker, Herschel; Brozek, Gary; Maxfield, Charlene (2009). Breaking Free: My Life with Dissociative Identity Disorder. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1416537502. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hoppes, Lynn. "After MMA, Herschel Walker thinks about public office – Page 2". ESPN. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Herschel Walker's son pursues competitive cheerleading". CBS News. May 4, 2015. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Trojan 70's". Johnson County Trojans Website. September 19, 2007. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ^ Scherr, Rich (December 19, 1992). "Dulaney's White wins national Dial Award Runner-swimmer Athlete of Year". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Herschel Walker". Trackingfootball.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Kaczynski, Andrew; Steck, Em (April 1, 2022). "GOP Senate candidate Herschel Walker has been overstating his academic achievements for years". CNN. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (May 24, 2022). "Herschel Walker's campaign falsely claimed he graduated from college". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Dale, Daniel; Kaczynski, Andrew (May 25, 2022). "Fact check: Herschel Walker falsely claims he never falsely claimed he graduated from University of Georgia". CNN. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg. "Herschel Walker's campaign falsely claimed he graduated from college". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Herschel Walker Graduates from UGA 40 Years Later".

- ^ a b "Inductee | Herschel Junior Walker 1999 | College Football Hall of Fame". College Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Wine, Steven (January 3, 2012). "Orange Bowl: Clemson freshman receiver Sammy Watkins has West Virginia worried". The Salt Lake Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ "5 things about Donald Trump's USFL adventure". ESPN. July 14, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ "1985 NFL Draft Listing". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Pro Football: Cowboy Streak Ends as Eagles Win, 23–21". Los Angeles Times. December 15, 1986. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "No Trade Underneath Tony Dorsett's Tree". Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ "Herschel Walker 1988 Game Log". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "1987 NFL Pro Bowlers". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "1988 NFL Pro Bowlers". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Herschel Walker trade: Boon for Cowboys, bust for Vikings". NFL.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "Wulf: The run that birthed Dallas' dynasty". ESPN. October 8, 2014. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ "NFL's 10 worst trades ever § Herschel Walker to Vikings, 1989". Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Viking Update Staff (June 20, 2001). "History: Walker Trade". Scout.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Reusse, Patrick (November 22, 2006). "Banquet packs 'em in, winner drives 'em out". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ "Walker signs with Eagles - UPI Archives". UPI. June 22, 1992. Retrieved January 5, 2025.

- ^ "Herschel Walker 1992 Game Log". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Divisional Round - Philadelphia Eagles at Dallas Cowboys - January 10th, 1993". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "Herschel Walker 1993 Game Log". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ "1993 Philadelphia Eagles Rosters, Stats, Schedule, Team Draftees". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Timothy W. (June 19, 1996). "Pro Football: Giants Release Walker, Shedding Third Veteran". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "1995 New York Giants Rosters, Stats, Schedule, Team Draftees". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Drozdiak, William (February 20, 1992). "HERSCHEL WALKER REPLACED ON U.S. FOUR-MAN BOBSLED TEAM". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- ^ "Herschel Walker Named To 2-Man Bobsled Team". The New York Times. January 30, 1992. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Episode 109". Inside MMA. November 9, 2007. HDNet. Archived from the original on November 22, 2007.

- ^ Hendricks, Maggie (September 21, 2009). "Former NFLer Herschel Walker signed with Strikeforce". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ Chiappetta, Mike (December 4, 2009). "Herschel Walker Begins AKA Training for Jan. 30 Strikeforce Debut". MMAFighting.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ "Nearing 50, Renaissance jock Herschel Walker breaks fitness rules". CNN. October 11, 2010. Archived from the original on October 12, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ Gentile, Kathy (January 30, 2010). "Match Results" (PDF). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida State Boxing Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ Pishna, Ken (November 6, 2010). "Herschel Walker Faces Scott Carson in MMA Return for Strikeforce". MMAWeekly.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ Al-Shatti, Shaun (December 12, 2011). "Herschel Walker Hoping For One Final Fight Despite Worries From Family – MMA Nation". Mma.sbnation.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Walker opens eatery". The Indiana Gazette. January 18, 1984. p. 25. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Hounshell, Blake (June 14, 2022). "The Strange Tale of Herschel Walker and the Chicken Empire That Wasn't". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Bryan Salvage (June 30, 2009). "Herschel Walker makes run at meat processing". Meat+Poultry. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jackson, Dylan; Bluestein, Greg (March 11, 2022). "Herschel Walker's business record reveals creditor lawsuits, exaggerated claims". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Slodysko, Brian; Barrow, Bill; Bleiberg, Jake (July 24, 2021). "As Herschel Walker eyes Senate run, a turbulent past emerges". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Ecarma, Caleb (May 24, 2022). "The GOP needs the Trump-loving football champ Herschel Walker to be Teflon". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Scipioni, Jade (April 26, 2018). "This Heisman Trophy winner now employs more than 800 people". Fox Business. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Eric (April 16, 2020). "Herschel Walker not relying on PPP, government to save his Georgia chicken business". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Richards, Doug (January 27, 2022). "Herschel Walker mocked businesses that took PPP money, even though he used it himself: report". 11Alive.com. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A.; Goldmacher, Shane (September 22, 2022). "Herschel Walker's Company Said It Donated Profits, but Evidence Is Scant". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Sean (May 28, 2014). "Football great Herschel Walker joins the ranks of Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ Kish, Phillip (November 2, 2018). "Herschel Walker endorses Brian Kemp for Georgia Governor". 11alive.com. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^

- Peter, Josh (August 29, 2015). "Herschel Walker: Donald Trump is 'my frontrunner' for president". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 23, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- Coleman, Justine (August 24, 2020). "Herschel Walker: Racism isn't Donald Trump". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "Highlights from RNC Night 1". CNN. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Cody Benjamin, President Trump appoints Bill Belichick, Herschel Walker to his new sports council Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, CBS Sports (May 4, 2018)

- ^ "Council Members, President's Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Judd, Donald; Vazquez, Maegan (March 23, 2022). "Biden requests Mehmet Oz and Herschel Walker resign from presidential council or be terminated". CNN. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ King, Michael (October 16, 2020). "Georgia football legend endorses Loeffler for US Senate". 11Alive.com. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Alex; Raju, Manu (April 22, 2021). "With Trump's backing, Walker freezes Senate GOP field in Georgia". CNN. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Patricia Murphy, Greg Bluestein & Tia Mitchell, The Jolt: Herschel Walker rumors blocking top Republicans in Senate race Archived April 27, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Atlanta Journal-Constitution (April 23, 2021)

- ^ Bill Barrow (June 26, 2021). "In Georgia, Herschel Walker puts GOP in a holding pattern". APNews. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ "Potential Herschel Walker Senate run in Georgia raising some GOP concerns". Fox News. July 6, 2021. Archived from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Warren, Michael; Stracqualursi, Veronica (October 27, 2021). "McConnell endorses Herschel Walker's Senate bid in sign of growing GOP establishment support". CNN. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Allison, Natalie (November 1, 2021). "Poll shows Herschel Walker far ahead in Georgia Senate primary". POLITICO. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c McCaffrey, Shannon (June 13, 2022). "Herschel Walker said he worked in law enforcement — he didn't". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ King, Maya; Vigdor, Neil (October 15, 2022). "What Was That Badge Herschel Walker Flashed in His Debate?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Fowler, Stephen (July 12, 2022). "Herschel Walker's 'bad air' comments the latest in series of policy gaffes". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Eskind, Amy (July 26, 2022). "Off the Field, Herschel Walker Fumbles: Inside the Hail Mary Attempt to Have a Football Star Flip the Senate: Walker, a former NFL player and close friend of Donald Trump, has taught a master class in self-destruction during his GOP-backed campaign to unseat Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock". People. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Cilizza, Chris (July 12, 2022). "Herschel Walker just proved (again) what a massive risk he is for Republicans". CNN. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Orr, Gabby; Warren, Michael (October 7, 2022). "Herschel Walker's campaign fires its political director in key Georgia Senate race". CNN. Archived from the original on October 7, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- ^ "Warnock and Walker clash over abortion, family strife and more in high-stakes Senate debate". NBC News. October 15, 2022. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ King, Maya; Weisman, Jonathan (October 14, 2022). "Walker Barrels Into Georgia Debate and Meets a Controlled Warnock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Jamerson, Lindsay Wise and Joshua (October 14, 2022). "Herschel Walker, Raphael Warnock Spar Over Abortion, Inflation in Lone Georgia Senate Debate". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Krieg, Dan Merica, Gregory (October 14, 2022). "Five takeaways from the Georgia Senate debate". CNN. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ King, Maya; Vigdor, Neil (October 15, 2022). "What Was That Badge Herschel Walker Flashed in His Debate?". The New York Times.

- ^ Wells, Dylan; Linskey, Annie (October 14, 2022). "Walker, Warnock clash over abortion, trustworthiness at Georgia debate". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Stanage, Niall (October 15, 2022). "The Memo: Walker gives GOP hope with Georgia debate performance". The Hill. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Folmar, Chloe (December 2, 2022). "Obama mocks Herschel Walker over werewolf, vampire talk". The Hill. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Kertscher, Tom (December 1, 2022). "Ad Watch: The context of Herschel Walker's comments about vampires, a bull, China's air". PolitiFact. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (November 17, 2022). "Herschel Walker says in rambling speech he wants to be 'werewolf, not vampire'". The Guardian. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "Georgia Senate race: Live updates and results in election between Raphael Warnock, Herschel Walker". Fox News. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "December 6, 2022 - General Election Runoff Official & Complete Results". Georgia Secretary of State. December 9, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ "'We put up one heck of a fight': Walker concedes Senate runoff to Warnock". Fox 5 Atlanta. December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dale, Daniel (August 28, 2021). "Fact check: Georgia candidate Herschel Walker is a serial promoter of false 2020 conspiracy theories". CNN. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (July 15, 2021). "Georgia Republicans center campaigns on false claims of election fraud". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 9, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Ford, Wayne (July 21, 2022). "U.S. Senate candidate Herschel Walker speaks during livestock auction at Athens cattle barn". Athens Banner-Herald. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Lerer, Lisa; King, Maya (October 15, 2022). "Five Key Moments From the Walker-Warnock Debate in Georgia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan (May 19, 2022). "As he runs in the G.O.P. primary for Georgia Senate, Herschel Walker says he wants a ban on abortion with no exceptions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Lonas, Lexi (May 20, 2022). "Herschel Walker says he wants total ban on abortion: 'There's no exception in my mind'". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ McCaffrey, Shannon (July 21, 2022). "Herschel Walker downplays abortion ruling's impact". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg; McCaffrey, Shannon (September 14, 2022). "Herschel Walker backs 15-week proposed abortion ban that's divided Republicans". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Samuels, Alex (November 3, 2022). "What Happens If Georgia's Senate Race Goes To A Runoff — Again?". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Walker softens stance on abortion in sole debate with Warnock". POLITICO. October 14, 2022. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b King, Maya (October 3, 2022). "Herschel Walker Paid for Girlfriend's Abortion, Report Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Barrow, Bill (October 4, 2022). "Herschel Walker paid for girlfriend's abortion, report says". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c Richards, Zoë; Caputo, Marc (October 4, 2022). "Herschel Walker's son lashes out at dad after news report the Senate GOP nominee paid for an abortion in 2009". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ "Republican Herschel Walker pledges to sue over report he paid for abortion". The Guardian. October 4, 2022. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "Trump and GOP defend Herschel Walker after abortion accusation rocks Georgia Senate race". October 4, 2022. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "Report: Mom of Walker's child says he paid for her abortion". Associated Press. October 6, 2022. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (October 6, 2022). "Herschel Walker faces another abortion report that threatens his Senate campaign". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d King, Jonah E. Bromwich, Maya; Lerer, Lisa; Bromwich, Jonah (October 7, 2022). "Herschel Walker Urged Woman to Have a 2nd Abortion, She Says". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Caputo, Marc (October 8, 2022). "Texts show family strife between Herschel Walker's wife and woman who alleged he paid for her abortion". NBC News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Chan, Stella; Krieg, Gregory (October 26, 2022). "Unnamed woman alleges Herschel Walker pressured her into an abortion in 1993". CNN. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan; King, Maya (October 26, 2022). "Unnamed Woman Says Walker Pressured and Paid for Her to Have Abortion in '93". The New York Times. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Sabrina (November 22, 2022). "Second woman renews accusation Walker pressured her to have abortion". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Mayorquin, Orlando (May 18, 2022). "Who is Herschel Walker? The former football star is running for Senate in Georgia as a Republican". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Wagner, John (August 22, 2022). "Walker, criticizing climate law, asks: 'Don't we have enough trees around here?'". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 22, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ Jones, Emily (November 16, 2022). "Herschel Walker on the environment: America needs its 'gas-guzzling cars'". Grist. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Cillizza, Chris (May 26, 2022). "Herschel Walker's answer on gun violence is literally nonsensical". CNN. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (June 3, 2022). "This is an absolutely savage new ad against Herschel Walker". CNN. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ a b McCaffrey, Shannon; Bluestein, Greg (September 27, 2022). "Why Herschel Walker is focusing on transgender athletes in Senate campaign". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ^ Andrew, Mike (May 27, 2022). "States should control Gay marriage, says GA senate candidate". Seattle Gay News. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/trump-nominates-ex-us-senate-candidate-herschel-walker-ambassador-bahamas-2024-12-18/

- ^ Niesse, Mark. "Walker's wife voted in Georgia as couple lives in Texas, records show". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Carlisle, Candace (October 27, 2015). "Former home of NFL legend Herschel Walker lands on the market for $3.25M". Dallas Business Journal. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg. "Herschel Walker registers to vote in Georgia as he weighs U.S. Senate run". Political Insider (The Atlanta Journal-Constitution). Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Kaczynski, Andrew; Alafriz, Olivia (November 29, 2022). "Georgia Senate candidate Herschel Walker described himself as living in Texas during 2022 campaign speech | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ Kaczynski, Andrew; Steck, Em (November 23, 2022). "Georgia Senate candidate Herschel Walker getting tax break in 2022 on Texas home intended for primary residence". CNN. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ King, Maya (November 23, 2022). "Herschel Walker, Running in Georgia, Receives Tax Break for Texas Residents". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Spearman, Kahron (December 16, 2020). "Former Heisman Trophy winner's son trends for wildly conspiratorial pro-Trump rant". The Daily Dot. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Colyar, Brock (March 31, 2021). "Zooming With TikTok's Right-Wing Pundit". Intelligencer. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Herschel Walker: 'Tell the World My Truth'". ABC News. April 14, 2008. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Herschel Walker has four children, not just one". CNN. June 16, 2022. Archived from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c King, Maya (June 16, 2022). "Herschel Walker Acknowledges Two More Children He Hadn't Mentioned". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Colvin, Jill (June 19, 2022). "Herschel Walker says he 'never denied' having 4 children". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Niquette, Mark (July 11, 2022). "Herschel Walker Hires GOP Veterans After Stumbles in Georgia Senate Race". Bloomberg News. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg; McCaffrey, Shannon (July 7, 2022). "Controversies mount for Herschel Walker, but impact is questionable". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on August 14, 2022.

- ^ Mangan, Dan; Breuninger, Kevin (June 16, 2022). "GOP Georgia Senate nominee Herschel Walker admits having 2 more 'secret' children — now says he has 4 kids". CNBC. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Shepherd, Brittany (October 5, 2022). "Christian Walker says father Herschel Walker's campaign 'has been a lie'". ABC News. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Heavey, Susan; Morgan, David (October 5, 2022). "Republican U.S. Senate hopeful Herschel Walker denies report he paid for abortion". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Hurt, Emma; Treene, Alayna (October 5, 2022). "Herschel Walker's ticking time bomb". Axios. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Slodysko, Brian (February 12, 2022). "Police records complicate Herschel Walker's recovery story". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Falco, Miriam. "Herschel Walker reveals many sides of himself". CNN. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Prater, Nia (October 4, 2022). "Herschel Walker's Son Goes Nuclear on His 'Lying' Father". New York. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ a b McCaffrey, Shannon; Bluestein, Greg (October 4, 2022). "Herschel Walker's campaign in turmoil as adult son accuses him of violence, lying". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ "Herschel Walker's son accuses father of lying about his past". Axios. October 4, 2022. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ Blaine, Kyle (December 1, 2022). "Woman alleges to Daily Beast that Herschel Walker was violent with her in 2005". CNN. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ Daniels, Cheyenne (December 1, 2022). "New pro-Warnock ad focuses on Walker's alleged violent past". The Hill. Retrieved December 2, 2022.

- ^ "Herschel Walker shares his battle against mental illness with Fort Drum Soldiers". U.S.Army. February 22, 2013. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Walker, Herschel; Gary Brozek; Charlene Maxfield (2008). Breaking free (1st Touchstone and Howard books hardcover ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1416537489. OCLC 173509294.

- ^ "Herschel Walker reveals many sides of himself". CNN. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Stern TA, Fava M, MD, Wilens TE, MD, Rosenbaum JF (2015). Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 395–397. ISBN 978-0-323-29507-9.

- ^ Lynn, S.J.; Berg, J.; Lilienfeld, S.O.; Merckelbach, H.; Giesbrecht, T.; Accardi, M.; Cleere, C. (2012). "Chapter14 - Dissociative disorders". In Hersen, M.; Beidel, D.C. (eds.). Adult Psychopathology and Diagnosis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 497–538. ISBN 978-1-118-13882-3.

- ^ Blihar D, Delgado E, Buryak M, Gonzalez M, Waechter R (September 2019). "A systematic review of the neuroanatomy of dissociative identity disorder". European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 9 (3): 100148. doi:10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100148.

- ^ a b c Golan, Casey; Devine, Curt; Chapman, Isabelle (September 2, 2021). "As Herschel Walker eyes Georgia US Senate seat, a newly revealed stalking claim brings his troubled history under scrutiny". CNN. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Kaczynski, Andrew; Steck, Em (April 1, 2022). "GOP Senate candidate Herschel Walker has been overstating his academic achievements for years | CNN Politics". CNN. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ Wade, Larry (July 14, 1983). "American Academy of Achievement fills Coronado with famous names" (PDF). Coronado Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "General Primary/Special Election - Official & Complete Results". Georgia Secretary of State. May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "United States Senate - November 8, 2022 General Election". Georgia Secretary of State. November 12, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "December 6, 2022 - General Election Runoff Unofficial Results". Georgia Secretary of State. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1962 births

- Living people

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen

- 21st-century evangelicals

- African-American Christians

- African-American men in politics

- All-American college football players

- American athlete-politicians

- American conspiracy theorists

- American evangelicals

- American football running backs

- American football return specialists

- American male taekwondo practitioners

- American male mixed martial artists

- American people who fabricated academic degrees

- The Apprentice contestants

- Bobsledders at the 1992 Winter Olympics

- Black conservatism in the United States

- Candidates in the 2022 United States Senate elections

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Dallas Cowboys players

- Georgia Bulldogs football players

- Georgia (U.S. state) Republicans

- Heisman Trophy winners

- Maxwell Award winners

- Minnesota Vikings players

- National Conference Pro Bowl players

- New Jersey Generals players

- New York Giants players

- Participants in American reality television series

- People from Johnson County, Georgia

- People with dissociative identity disorder

- Philadelphia Eagles players

- Players of American football from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Texas Republicans

- United States Football League MVPs

- Players of American football from Augusta, Georgia

- Walter Camp Award winners

- Southeastern Conference Athlete of the Year winners

- African-American candidates for the United States Senate