Sammy Davis Jr.

Sammy Davis Jr. | |

|---|---|

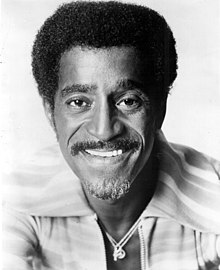

Davis in 1972 | |

| Born | Samuel George Davis Jr. December 8, 1925 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | May 16, 1990 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1928–1990[1] |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 4 |

| Parents | |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Rat Pack |

| Website | sammydavisjr |

Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) was an American singer, actor, comedian, dancer, and musician.

At age two, Davis began his career in Vaudeville with his father Sammy Davis Sr. and the Will Mastin Trio, which toured nationally, and his film career began in 1933. After military service, Davis returned to the trio and became a sensation following key nightclub performances at Ciro's (in West Hollywood) in 1951, including one after the Academy Awards ceremony. With the trio, he became a recording artist. In 1954, at the age of 29, he lost his left eye in a car accident. Several years later, he converted to Judaism, finding commonalities between the oppression experienced both by black Americans and Jewish communities.[2] In 1958, he faced a backlash for his involvement with a white woman at a time when interracial relationships were taboo in the U.S. and when interracial marriage was not legalized nationwide until 1967.[3]

Davis had a starring role on Broadway in Mr. Wonderful with Chita Rivera (1956). In 1959, the Canadian Broadcasting Company provided Sammy Davis Jr. with an opportunity he couldn't get in his own country: the chance to host his own TV show, Parade. In 1960, he appeared in the Rat Pack film Ocean's 11. He returned to the stage in 1964 in a musical adaptation of Clifford Odets's Golden Boy. Davis was nominated for a Tony Award for his performance. The show featured the first interracial kiss on Broadway.[4] In 1966, he had his own TV variety show, titled The Sammy Davis Jr. Show. While Davis's career slowed in the late 1960s, his biggest hit, "The Candy Man", reached the top of the Billboard Hot 100 in June 1972, and he became a star in Las Vegas, earning him the nickname "Mister Show Business".[5] Davis's popularity helped break the race barrier of the segregated entertainment industry.[6] One day on a golf course with Jack Benny, he was asked what his handicap was. "Handicap?" he asked. "Talk about handicap. I'm a one-eyed Negro who's Jewish."[7][8] This was to become a signature comment.[9]

After reuniting with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin in 1987, Davis toured with them and Liza Minnelli internationally, before his death in 1990. He died in debt to the Internal Revenue Service,[10] and his estate was the subject of legal battles after the death of his wife.[11] His final album was a Country Music Album, a departure from his usual musical style.[12] Davis was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP and was nominated for a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy Award for his television performances. He was a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1987, and in 2001, he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2017, Davis was inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Early life

[edit]

Davis was born on December 8, 1925, in the Harlem district of Manhattan in New York City, the son of African American entertainer and stage performer Sammy Davis Sr. (1900–1988) and Cuban-American tap dancer and stage performer Elvera Sanchez (1905–2000).[13] During his lifetime, Davis stated that his mother was Puerto Rican and born in San Juan. However, in the 2003 biography In Black and White, author Wil Haygood wrote that Davis's mother was born in New York City to Cuban parents who were of Afro-Cuban background, and that Davis claimed he was Puerto Rican because he feared anti-Cuban backlash would hurt his record sales.[14][15] Davis's parents were vaudeville dancers. As an infant, he was reared by his paternal grandmother. When he was three years old, his parents separated. His father, not wanting to lose custody of his son, took him on tour. Davis learned to dance from his father and his godfather Will Mastin. Davis joined the act as a child, and they became the Will Mastin Trio. Throughout his career, Davis included the Will Mastin Trio in his billing. Mastin and his father shielded him from racism, for example by dismissing race-based snubs as jealousy. However, when Davis served in the United States Army during World War II, he was confronted by strong prejudice. He later said: "Overnight the world looked different. It wasn't one color any more. I could see the protection I'd gotten all my life from my father and Will. I appreciated their loving hope that I'd never need to know about prejudice and hate, but they were wrong. It was as if I'd walked through a swinging door for 18 years, a door which they had always secretly held open."[16] At age seven, Davis played the title role in the film Rufus Jones for President, in which he sang and danced with Ethel Waters.[17] He lived for several years in Boston's South End and reminisced years later about "hoofing and singing" at Izzy Ort's Bar & Grille.[18]

Military service

[edit]In 1944, during World War II, Davis was drafted into the U.S. Army at age 18.[19] He was frequently abused by white soldiers from the South and later recounted: "I must have had a knockdown, drag-out fight every two days." His nose was broken numerous times and permanently flattened. At one point he was offered a beer laced with urine.[6]

He was reassigned to the Army's Special Services branch, which put on performances for troops.[20] At one show he found himself performing in front of soldiers who had previously racially abused him.[19] Davis, who earned the American Campaign Medal and World War II Victory Medal, was discharged in 1945 with the rank of private.[19] He later said, "My talent was the weapon, the power, the way for me to fight. It was the one way I might hope to affect a man's thinking."[21]

Career

[edit]1940s

[edit]Following his discharge from the Army, Davis rejoined the family dance act, which played at clubs around Portland, Oregon. He also recorded blues songs for Capitol Records in 1949 under the pseudonyms Shorty Muggins and Charlie Green.[22]

1950s

[edit]In March 1951, the Will Mastin Trio appeared at Ciro's as the opening act for headliner Janis Paige. They were to perform for only 20 minutes, but the reaction from the celebrity-filled crowd was so enthusiastic, especially when Davis launched into his impressions, that they performed for nearly an hour, and Paige insisted the order of the show be flipped.[6] Davis began to achieve success on his own and was singled out for praise by critics, releasing several albums.[23]

In 1953, Davis was offered his own television show on ABC, Three for the Road—with the Will Mastin Trio.[24][25][26] The network spent $20,000 filming the pilot, which presented African Americans as struggling musicians, not slapstick comedy or the stereotypical mammy roles of the time. The cast included Frances Davis, who was the first black ballerina to perform for the Paris Opera, actresses Ruth Attaway and Jane White, and Frederick O'Neal, who founded the American Negro Theater. The network could not get a sponsor, so the show was dropped.[26]

In 1954, Davis was hired to sing the title song for the Universal Pictures film Six Bridges to Cross.[27][28] In 1956, he starred in the Broadway musical Mr. Wonderful, which was panned by critics but was a commercial success, closing after 383 performances.[29]

In 1958, Davis was hired to crown the winner of the Miss Cavalcade of Jazz beauty contest for the famed fourteenth Cavalcade of Jazz concert produced by Leon Hefflin Sr., held at the Shrine Auditorium on August 3. The other headliners were Little Willie John, Sam Cooke, Ernie Freeman, and Bo Rhambo. The event featured the top four prominent disc jockeys of Los Angeles.[30][31]

In 1959, Davis became a member of the Rat Pack, led by his friend Frank Sinatra, which included fellow performers Dean Martin, Joey Bishop, and Peter Lawford, a brother-in-law of John F. Kennedy. Initially, Sinatra called the gathering "the Clan", but Davis voiced his opposition, saying that it reminded people of the Ku Klux Klan. Sinatra renamed the group "the Summit". One long night of poker that went on into the early morning saw the men drunken and disheveled. As Angie Dickinson approached the group, she said, "You all look like a pack of rats." The nickname caught on, and they were then called the Rat Pack, the name of the earlier group led by Humphrey Bogart and his wife, Lauren Bacall, who originally made the remark about the "pack of rats" they associated with.

1960s

[edit]The group around Sinatra made several movies together, including Ocean's 11 (1960), Sergeants 3 (1962), and Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), and they performed onstage together in Las Vegas. In 1964, Davis was the first African American to sing at the Copacabana night club in New York.[32]

Davis was a headliner at The Frontier Casino in Las Vegas, but owing to Jim Crow practices in Las Vegas, he was required (as were all black performers in the 1950s) to lodge in a rooming house on the west side of the city instead of in the hotels as his white colleagues did. No dressing rooms were provided for black performers, and they had to wait outside by the swimming pool between acts. Davis and other black artists could entertain but could not stay at the hotels where they performed, gamble in the casinos, or dine or drink in the hotel restaurants and bars. Davis later refused to work at places that practiced racial segregation.[33]

Canada provided opportunities for performers like Davis unable to break the color barrier in U.S. broadcast television, and in 1959 he starred in his own TV special, Sammy's Parade, on the Canadian network CBC.[34] It was a breakthrough event for the performer, as in the United States in the 1950s corporate sponsors largely controlled the screen: "Black people [were] not portrayed very well on television, if at all", according to Jason King of the Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music.[35]

In 1964, Davis was starring in Golden Boy at night and shooting his own New York-based afternoon talk show during the day.[citation needed] When he could get a day off from the theater, he recorded songs in the studio, performed at charity events in Chicago, Miami, or Las Vegas, or appeared on television variety specials in Los Angeles. Davis felt he was cheating his family of his company, but he said he was incapable of standing still.

On December 11, 1967, NBC broadcast a musical-variety special featuring Nancy Sinatra, the daughter of Frank Sinatra, titled Movin' with Nancy. In addition to the Emmy Award-winning musical performances, the show is notable for Nancy Sinatra and Davis greeting each other with a kiss, one of the first black-white kisses in US television.[36]

Davis had a friendship with Elvis Presley in the late 1960s, as they both were top-draw acts in Las Vegas at the same time. Davis was in many ways just as reclusive during his hotel gigs as Elvis was, holding parties mainly in his penthouse suite that Elvis occasionally attended. Davis sang a version of Presley's song "In the Ghetto" and made a cameo appearance in Presley's 1970 concert film Elvis: That's the Way It Is. One year later, he made a cameo appearance in the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever, but the scene was cut. In Japan, Davis appeared in television commercials for coffee and Suntory Whiskey. In the United States he joined Sinatra and Martin in a radio commercial for a Chicago car dealership.

Although he was still popular in Las Vegas, he saw his musical career decline by the late 1960s. He had a No. 11 hit (No. 1 on the Easy Listening singles chart) with "I've Gotta Be Me" in 1969. He signed with Motown to update his sound and appeal to young people.[37]

1970s–1980s

[edit]

Davis had an unexpected No. 1 hit with "The Candy Man" with MGM Records in 1972. He did not particularly care for the song and was chagrined that he had become known for it, but Davis made the most of his opportunity and revitalized his career. Although he enjoyed no more Top 40 hits, he did enjoy popularity with his 1976 performance of the theme song from the Baretta television series, "Baretta's Theme (Keep Your Eye on the Sparrow)" (1975–1978), which was released as a single (20th Century Records).

On May 27–28, 1973, Davis hosted (with Monty Hall) the first annual 20-hour Highway Safety Foundation telethon. Guests included Muhammad Ali, Paul Anka, Jack Barry, Joyce Brothers, Ray Charles, Dick Clark, Roy Clark, Howard Cosell, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Joe Franklin, Cliff Gorman, Richie Havens, Danny Kaye,[38] Jerry Lewis, Hal Linden, Rich Little, Butterfly McQueen, Minnie Pearl, Boots Randolph, Tex Ritter, Phil Rizzuto, The Rockettes, Nipsey Russell, Sally Struthers, Mel Tillis, Ben Vereen, and Lawrence Welk. It was a financial disaster. The total amount of pledges was $1.2 million. Actual pledges received were $525,000.[39]

Davis was a huge fan of daytime television, particularly the soap operas produced by the American Broadcasting Company. He made a cameo appearance on General Hospital and had a recurring role as Chip Warren on One Life to Live, for which he received a 1980 Daytime Emmy Award nomination. He was also a game show fan, appearing on Family Feud in 1979 and Tattletales with his wife Altovize in the 1970s.

In 1988, Davis was billed to tour with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, but Sinatra and Martin had a falling out.[40] Liza Minnelli replaced Martin on the tour dubbed as ''The Ultimate Event''.[41][42] During the tour in 1989, Davis was diagnosed with throat cancer; his treatments prevented him from performing.[43][44]

Political beliefs and activism

[edit]

Davis was a registered Democrat and supported John F. Kennedy's 1960 election campaign as well as Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 campaign.[45] He went on to become a close friend of President Richard Nixon (a Republican) and publicly endorsed him at the 1972 Republican National Convention.[45] Davis also made a USO tour to South Vietnam at Nixon's request.

In February 1972, during the later stages of the Vietnam War, Davis went to Vietnam to observe military drug abuse rehabilitation programs and talk to and entertain the troops. He did this as a representative from President Nixon's Special Action Office For Drug Abuse Prevention.[46] He performed shows for up to 15,000 troops; after one two-hour performance he reportedly said, "I've never been so tired and felt so good in my life."[47] The U.S. Army made a documentary about Davis's time in Vietnam performing for troops on behalf of Nixon's drug treatment program.[48]

Nixon invited Davis and his wife Altovize to sleep in the White House in 1973, the first time African Americans were invited to do so. The Davizes spent the night in the Lincoln Bedroom.[49] Davis later said he regretted supporting Nixon, accusing him of making promises on civil rights that he did not keep.[50]

- "By early 1973, a desperate Sy Marsh (Davis's agent) told (Jesse) Jackson that Davis really needed help getting out of the Nixon imbroglio (1972 reelection endorsement). "Jesse (Jackson) said, 'If you can come up with $25,000 for my charity (Operation PUSH), then (have Davis) come to Chicago,'" Marsh recalls."[51]

Davis later supported Jesse Jackson's 1984 campaign for president.[52]

Personal life

[edit]Accident and conversion to Judaism

[edit]

Davis nearly died in an automobile accident on November 19, 1954, in San Bernardino, California, as he was making a return trip from Las Vegas to Los Angeles.[53] During the previous year, he had started a friendship with comedian and host Eddie Cantor, who had given him a mezuzah. Instead of putting it by his door as a traditional blessing, Davis wore it around his neck for good luck. The only time he forgot it was the night of the accident.[54]

The accident occurred at a fork in U.S. Route 66 at Cajon Boulevard and Kendall Drive, when a driver, who missed turning at the fork, backed up her car in Davis's lane and he drove into her car.[55] Davis consequently lost his left eye to the bullet-shaped horn button (a standard feature in 1954 and 1955 Cadillacs). His friend, actor Jeff Chandler, said he would give one of his own eyes to keep Davis from total blindness.[56] He wore an eye patch for at least six months following the accident.[57][58] The singer was featured with the patch on the cover of his debut album and appeared on What's My Line? wearing the patch.[59] Later, Davis was fitted for a glass eye, which he wore for the rest of his life.

In the hospital, Eddie Cantor described to Sammy the similarities between Jewish and Black cultures. Davis, born to a Catholic mother and Baptist father, was raised Catholic and began studying Jewish history as an adult, converting to Judaism several years later in 1960.[7][60][61] One passage from his readings (from the book A History of the Jews by Abram L. Sachar), describing the endurance of the Jewish people, interested him in particular: "The Jews would not die. Three millennia of prophetic teaching had given them an unwavering spirit of resignation and had created in them a will to live which no disaster could crush."[62] The accident marked a turning point in Davis's career, taking him from a well-known entertainer to a national celebrity.[63]

Relationships and marriages

[edit]In 1957, Davis was involved with actress Kim Novak, who was under contract with Columbia Pictures. Because Novak was white, Harry Cohn, the president of Columbia, gave in to his worries that backlash against the relationship could hurt the studio. There are several accounts of what happened, but they agree that Davis was threatened by organized crime figures close to Cohn.[64] According to one account, Cohn called racketeer John Roselli, who was told to inform Davis that he must stop seeing Novak. To try to scare Davis, Roselli had him kidnapped for a few hours.[65] Another account relates that the threat was conveyed to Davis's father by mobster Mickey Cohen.[64] Davis was threatened with the loss of his other eye or a broken leg if he did not marry a black woman within two days. Davis sought the protection of Chicago mobster Sam Giancana, who said that he could protect him in Chicago and Las Vegas but not California.[6][64][66]

Davis briefly married black dancer Loray White in 1958 to protect himself from mob violence;[64] Davis had previously dated White, who was 23 and twice divorced and had a six-year-old child.[6] He paid her a lump sum – $10,000 or $25,000 – to engage in a marriage on the condition that it would be dissolved before the end of the year.[6][64] Davis became inebriated at the wedding and attempted to strangle White en route to their wedding suite. Checking on him later, Davis's personal assistant Arthur Silber Jr. found Davis with a gun to his head. Davis despairingly said to Silber, "Why won't they let me live my life?"[64] The couple never lived together[6] and commenced divorce proceedings in September 1958.[64] The divorce was granted in April 1959.[67]

In 1959, Davis had "a short, stormy, exciting relationship" with Nichelle Nichols.[28][68]

In 1960, there was another racially charged public controversy when Davis married white, Swedish-born actress May Britt in a ceremony officiated by Rabbi William M. Kramer at Temple Israel of Hollywood. While interracial marriage had been legal in California since 1948, anti-miscegenation laws in the U.S. still stood in 23 states, and a 1958 opinion poll revealed only 4% of Americans supported marriage between black and white spouses.[69] During 1964–66, Davis received racist hate mail while starring in the Broadway adaptation of Golden Boy, in which his character is in a relationship with a white woman, paralleling his own interracial relationship. At the time Davis appeared in the musical, although New York had no laws against it, debate about interracial marriage was still ongoing in America as Loving v. Virginia was being fought. It was only in 1967, after the musical finished, that anti-miscegenation laws in all states were ruled unconstitutional (via the 14th Amendment adopted in 1868) by the U.S. Supreme Court.[70]

May Britt's and Davis's daughter Tracey Davis (July 5, 1961 – November 2, 2020)[71][72][73][74] alleged in a 2014 book that the marriage to Britt also resulted in President Kennedy refusing to allow Davis to perform at his inauguration.[75] The snub was confirmed by director Sam Pollard, who revealed in a 2017 American Masters documentary that Davis's invitation to perform at the inauguration was abruptly canceled on the night of JFK's inaugural party.[76]

In addition to Tracey, Davis and Britt adopted two sons, Mark and Jeff.[2][77] Davis performed almost continuously and spent little time with his wife. They divorced in 1968 after Davis admitted to an affair with singer Lola Falana.[44][78][79]

In 1968, Davis started dating Altovise Gore, a dancer in Golden Boy. They were married on May 11, 1970, by Reverend Jesse Jackson and adopted a son, Manny, in 1989.[44] They remained married until his death in 1990.[80] By the end, Altovise Davis was sharing her mansion with her husband's girlfriend.[78]

Interests

[edit]Davis was an avid photographer who enjoyed shooting pictures of family and acquaintances. His body of work was detailed in a 2007 book by Burt Boyar titled Photo by Sammy Davis, Jr.[81] "Jerry [Lewis] gave me my first important camera, my first 35 millimeter, during the Ciro's period, early '50s", Boyar quotes Davis as saying "And he hooked me." Davis used a medium format camera later on to capture images. Boyar reports that Davis had said, "Nobody interrupts a man taking a picture to ask... 'What's that nigger doin' here?'". His catalog includes rare photos of his father dancing onstage as part of the Will Mastin Trio and intimate snapshots of close friends Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, James Dean, Nat "King" Cole, and Marilyn Monroe. His political affiliations also were represented, in his images of Robert Kennedy, Jackie Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. His most revealing work comes in photographs of wife May Britt and their three children, Tracey, Jeff and Mark.

Davis was an enthusiastic shooter and gun owner. He participated in fast-draw competitions. Johnny Cash recalled that Davis was said to be capable of drawing and firing a Colt Single Action Army revolver in less than a quarter of a second.[82] Davis was skilled at fast and fancy gunspinning and appeared on television variety shows showing off this skill. He also demonstrated gunspinning to Mark on The Rifleman in "Two Ounces of Tin". He appeared in western films and as a guest star on several television westerns.

Davis experimented with Satanism following his 1968 divorce.[44] He became a warlock in the Church of Satan and was a friend of its High Priest, Anton LaVey. Even after cutting ties with the Church, he continued to perform Satanic rituals.[83]

Davis was openly bisexual.[84]

Health

[edit]After Davis's marriage to May Britt ended in 1968, Davis turned to alcohol. He also "found solace in drugs, particularly cocaine and amyl nitrite" and experimented with pornography.[44][78]

After a bout with cirrhosis due to years of drinking,[40] Davis announced his sponsorship of the Sammy Davis Jr. National Liver Institute in Newark, New Jersey in 1985.[85]

Final illness and death

[edit]

In August 1989, Davis began to develop symptoms of cancer – a tickle in his throat and an inability to taste food.[86] Doctors found a malignant tumor in Davis's throat.[43][87] He was a heavy smoker and had often smoked up to four packs of cigarettes a day as an adult.[87] When told that surgery (laryngectomy) offered him the best chance of survival, Davis replied he would rather keep his voice than have a part of his throat removed; he was treated with definitive radiation therapy.[86] His larynx was later removed when his cancer recurred.[15][88] He was released from the hospital on March 13, 1990.[89]

Davis died of complications from throat cancer two months later at his home in Beverly Hills, California, on May 16, 1990, at age 64.[89] He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. On May 18, 1990, two days after his death, the neon lights of the Las Vegas Strip were darkened for ten minutes as a tribute.[90]

Estate

[edit]Davis left the bulk of his estate, estimated at $4,000,000 (U.S.), to his widow Altovise Davis,[80][91] but he owed the IRS $5,200,000, which after interest and penalties had increased to over $7,000,000.[92][93] Altovise became liable for his debt because they had filed jointly and she had co-signed their tax returns.[78] She was forced to auction his personal possessions and real estate. Some of his friends in the industry, including Quincy Jones, Joey Bishop, Ed Asner, Jayne Meadows, and Steve Allen, participated in a fundraising concert at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas.[92] Altovise and the IRS reached a settlement in 1997.[93] After she died in 2009, their son Manny was named executor of the estate and majority-rights holder of his intellectual property.[94]

Legacy

[edit]Portrayals

[edit]- SCTV's The Sammy Maudlin Show[95][96][97] sketches were inspired by the syndicated talk show called Sammy & Company (April 5, 1975 – March 19, 1977).[98][99][100][101]

- In an episode of Charlie's Angels, Davis had a dual role, playing both himself and a Sammy Davis Jr. impersonator who is kidnapped by mistake (in a comic relief scene, the impersonator beats up a candy machine which does not give him his candy, a spoof of Davis's song "The Candy Man").

- Comedian Jim Carrey has portrayed Davis on stage, in the 1983 film Copper Mountain, and in a stand-up routine.

- On Saturday Night Live, Davis has been portrayed by Garrett Morris, Eddie Murphy, Billy Crystal and Tim Meadows.

- Davis was portrayed on the popular sketch comedy show In Living Color by Tommy Davidson, notably a parody of the film Ghost, in which the ghost of Davis enlists the help of Whoopi Goldberg to communicate with his wife.

- David Raynr portrayed Davis in the 1992 miniseries Sinatra, a television film about the life of Frank Sinatra.

- In the comedy film Wayne's World 2 (1993), Tim Meadows portrays Davis in the dream sequence with Michael A. Nickles as Jim Morrison.

- In the sitcom Malcolm & Eddie (1996), Eddie Sherman (played by comedian Eddie Griffin) impersonates Davis in the episode "Sh-Boing-Boing" to help his partner Malcolm McGee (played by Malcolm-Jamal Warner) reconcile his grandparents' relationship.

- Davis was portrayed by Don Cheadle in the HBO film The Rat Pack, a 1998 television film about the group of entertainers. Cheadle won a Golden Globe Award for his performance.

- He was portrayed by Paul Sharma in the 2003 West End production Rat Pack Confidential.[102]

- Davis was portrayed in 2008 by Keith Powell in an episode of 30 Rock titled "Subway Hero".

- In September 2009, the musical Sammy: Once in a Lifetime premiered at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego with a book, music, and lyrics by Leslie Bricusse, and additional songs by Bricusse and Anthony Newley. The title role was played by Tony Award nominee Obba Babatundé.

- Comedian Billy Crystal has portrayed Davis on Saturday Night Live, in his stand-up routines, and at the 2012 Oscars.

- Actor Phaldut Sharma created the comedy web-series I Gotta Be Me (2015), following a frustrated soap star as he performs as Sammy in a Rat Pack tribute show.[103]

- In January 2017, Davis's estate joined a production team led by Lionel Richie, Lorenzo di Bonaventura, and Mike Menchel to make a movie based on Davis's life and show-biz career.[104]

Honors and awards

[edit]Shortly before his death in 1990, ABC aired the TV special Sammy Davis, Jr. 60th Anniversary Celebration, produced by George Schlatter. An all-star cast, including Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Eddie Murphy, Diahann Carroll, Clint Eastwood, and Ella Fitzgerald, paid tribute to Davis.[105] The show was nominated for six Primetime Emmy Awards, winning Outstanding Variety, Music or Comedy.[106]

Grammy Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Song | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Grammy Hall of Fame Award | "What Kind of Fool Am I?" | Inducted | Recorded in 1962 |

| 2001 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award | Winner | Posthumously | |

| 1972 | Pop Male Vocalist | "Candy Man" | Nominee | |

| 1962 | Record of the Year | "What Kind of Fool Am I?" | Nominee | |

| 1962 | Male Solo Vocal Performance | "What Kind of Fool Am I?" | Nominee |

Emmy Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Program | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Outstanding Variety, Music or Comedy | Sammy Davis Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration | Won |

| 1989 | Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series | The Cosby Show | Nominated |

| 1980 | Outstanding Cameo Appearance in a Daytime Drama Series | One Life to Live | Nominated |

| 1966 | Outstanding Variety Special | The Swinging World of Sammy Davis Jr. | Nominated |

| 1956 | Best Specialty Act — Single or Group | Sammy Davis Jr. | Nominated |

Other honors

[edit]| Year | Category | Organization | Program | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum | Inducted | ||

| 2017 | Singer | National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame | Inducted | |

| 2008 | International Civil Rights Walk of Fame | Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site | Inducted | |

| 2006 | Las Vegas Walk of Stars[107] | front of Riviera Hotel | Inducted | |

| 1989 | NAACP Image Award | NAACP | Winner | |

| 1987 | Kennedy Center Honors | John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts |

Honoree | |

| 1985 | Worst Supporting Actor | Golden Raspberry Awards | Cannonball Run II (1984) | Nominee |

| 1977 | Best TV Actor — Musical/Comedy | Golden Globe | Sammy and Company (1975) | Nominee |

| 1974 | Special Citation Award | National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences | Winner | |

| 1968 | NAACP Spingarn Medal Award | NAACP | Winner | |

| 1965 | Best Actor — Musical | Tony Award | Golden Boy | Nominee |

| 1961 | Man of the Year[108] | American Guild of Variety Artists | Winner | |

| 1960 | Recording[109] | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Inducted |

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- Starring Sammy Davis Jr. (1955)

- Just for Lovers (1955)

- Mr. Wonderful (1956)

- Here's Lookin' at You (1956)

- Sammy Swings (1957)

- Boy Meets Girl (with Carmen McRae) (1957)

- Sammy Jumps with Joya (with Joya Sherrill) (1957)

- It's All Over but the Swingin' (1957)

- Mood to Be Wooed (1958)

- All The Way... and Then Some! (1958)

- Porgy and Bess (with Carmen McRae) (1959)

- Sammy Awards (1960)

- I Gotta Right to Swing (1960)

- The Wham of Sam (1961)

- Mr. Entertainment (1961)

- Sammy Davis Jr. Belts the Best of Broadway (1962)

- The Sammy Davis Jr. All-Star Spectacular (1962)

- What Kind of Fool Am I and Other Show-Stoppers (1962)

- As Long as She Needs Me (1963)

- Sammy Davis Jr. Salutes the Stars of the London Palladium (1964)

- The Shelter of Your Arms (1964)

- Sammy Davis Jr. Sings Mel Tormé's "California Suite" (1964)

- Sammy Davis Jr. Sings the Big Ones for Young Lovers (1964)

- When the Feeling Hits You! (with Sam Butera and the Witnesses) (1965)

- Our Shining Hour (with Count Basie) (1965)

- If I Ruled the World (1965)

- The Nat King Cole Songbook (1965)

- Sammy's Back on Broadway (1965)

- The Sammy Davis Jr. Show (1966)

- Sammy Davis, Jr. Sings and Laurindo Almeida Plays (with Laurindo Almeida) (1966)

- Sammy Davis Jr. Sings the Complete "Dr. Dolittle" (1967)

- Lonely Is the Name (1968)

- I've Gotta Be Me (1968)

- The Goin's Great (1969)

- Something for Everyone (1970)

- Sammy Steps Out (1970)

- Now (1972)

- Portrait of Sammy Davis Jr. (1972)

- That's Entertainment! (1974)

- The Song and Dance Man (1976)

- Closest of Friends (1982)

Work on screen and stage

[edit]Filmography

[edit]- Rufus Jones for President (1933) – Rufus Jones

- Seasoned Greetings (1933) – Henry Johnson – Store Customer

- Sweet and Low (1947) – Member, Will Maston Trio

- Meet Me in Las Vegas (1956) – Sammy Davis Jr. (voice, uncredited)

- Anna Lucasta (1958) – Danny Johnson

- Porgy and Bess (1959) – Sportin' Life

- Ocean's 11 (1960) – Josh Howard

- Pepe (1960) – Sammy Davis Jr.

- Sergeants 3 (1962) – Jonah Williams

- The Rifleman (1962) – Tip Corey, Wade Randall

- Convicts 4 (1962) – Wino

- Three Penny Opera (1963) – Street Singer

- Johnny Cool (1963) – Educated

- Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964) – Will

- Nightmare in the Sun (1965) – Truck driver

- The Second Best Secret Agent in the Whole Wide World (1965, title song) – Singer behind opening credits (uncredited)

- A Man Called Adam (1966) – Adam Johnson

- Alice in Wonderland (or What's a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Place Like This?) (1966) – Cheshire Cat

- Salt and Pepper (1968) – Charles Salt

- The Fall (1969)

- The Pigeon (1969) – Larry Miller (unsold TV pilot produced by Aaron Spelling)

- Sweet Charity (1969) – Big Daddy

- One More Time (1970) – Charles Salt

- Elvis: That's the Way It Is (1970)

- The Trackers (1971) – TV movie with Ernest Borgnine

- Diamonds Are Forever (1971) – Casino Punter (deleted scene)

- Save the Children (1973)

- Poor Devil (1973; unsold pilot of a TV series)

- Gone with the West, also known outside the U.S. as Little Moon and Jud McGraw (1975) – Kid Dandy

- Madeleine (1977) – Spud The Scarecrow (singing voice)

- Sammy Stops the World (1978) – Littlechap

- The Cannonball Run (1981) – Morris Fenderbaum

- Heidi's Song (1982) – Head Ratte (voice)

- Cracking Up (1983)

- Broadway Danny Rose (1984) – Thanksgiving Parade's Grand Marshall (uncredited)

- Cannonball Run II (1984) – Morris Fenderbaum

- Alice in Wonderland (1985) – The Caterpillar / Father William

- That's Dancing! (1985)

- Knights of the City (1986)

- The Perils of P.K. (1986)

- Moon over Parador (1988)

- Tap (1989) – Little Mo

- Hanna-Barbera's 50th: A Yabba Dabba Doo Celebration – Himself (1989)

- The Kid Who Loved Christmas (1990) – Sideman (final film role)

Television

[edit]- What's My Line? – "Sammy Davis Jr." (1955)

- General Electric Theater – "The Patsy" (1960) Season 8 Episode 21

- Frontier Circus - episode Coals Of Fire (1961)

- Lawman – episode Blue Boss and Willie Shay" (1961)

- The Dick Powell Show – episode "The Legend" (1962)

- Hennesey – episode "Tight Quarters" (1962)

- The Rifleman – 2 episodes "Two Ounces of Tin (#4.21)" (February 19, 1962) and "The Most Amazing Man (#5.9)" (November 27, 1962)

- 77 Sunset Strip – episode "The Gang's All Here" (1962)

- Ben Casey – episode "Allie" (1963)

- The Patty Duke Show – episode "Will the Real Sammy Davis Please Hang Up?" (1965)

- The Sammy Davis Jr. Show – Host (January 7, 1966)

- Alice in Wonderland or What's a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (March 30, 1966)

- The Wild Wild West – episode "The Night of the Returning Dead" (October 14, 1966)

- Batman – "The Clock King's Crazy Crimes" (1966)

- I Dream of Jeannie – episode "The Greatest Entertainer in the World" (1967)

- Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In – Here Comes The Judge skit (1968–70, 1971, 1973)

- The Mod Squad – three episodes: "Keep the Faith Baby" (1969), "Survival House" (1970), and "The Song of Willie" (1970)

- The Beverly Hillbillies – episode Manhattan Hillbillies (1969)

- The Name of the Game – episode "I Love You, Billy Baker" (1970)

- Here's Lucy (1970)

- The Courtship of Eddie's Father – episode "A Little Help From My Friend" (1972)

- All in the Family – episode "Sammy's Visit" (1972)

- Chico and the Man – episode "Sammy Stops In" (1975)

- The Carol Burnett Show (1975)

- Sammy & Company – host/performer (1975–1977)

- Charlie's Angels – episode "Sammy Davis, Jr. Kidnap Caper" (1977)

- Sanford – episodes "Dinner and George's" (cameo) and "The Benefit" (1980)

- Archie Bunker's Place – episode "The Return of Sammy" (1980)

- General Hospital – episode Benefit for Sports Center (1982)

- General Hospital – Eddie Phillips (father to Bryan Phillips) (1983)

- Channel Seven Perth's Telethon (1983)

- The Jeffersons – episode "What Makes Sammy Run?" (1984)

- Fantasy Island – episode "Mr. Bojangles and the Dancer/Deuces are Wild" (1984)

- Gimme a Break! – episode "The Lookalike" (1985)

- Alice in Wonderland

- Hunter – episode "Ring of Honor" (1989)

- The Cosby Show – episode "No Way, Baby" (1989)

- Sammy Davis, Jr. 60th Anniversary Celebration (1990) – 21⁄2 hour all star TV special[110]

Theater

[edit]- Mr. Wonderful (1956), musical

- Golden Boy (1964), musical – Tony Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical

- Sammy (1974), special performance featuring Davis with the Nicholas Brothers

- Stop the World – I Want to Get Off (1978), musical revival

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Edward J. Boyer (May 17, 1990). "From the Archives: Consummate Entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Sammy Davis Jr. Biography. Biography.com. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Lanzendorfer, Joy (August 9, 2017) "Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star", Smithsonian. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "Paula Wayne, Golden-Voiced Broadway Star of Golden Boy, Dead at 84". Broadway.com. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Casey Kasem's American Top 40 – The 70's from April 29 & May 6, 1972.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kashner, Sam (September 2013). "The Color of Love". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Religion: Jewish Negro Time February 1, 1960.

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr. "Is My Mixed Marriage Mixing Up My Kids", Ebony, October 1966, p. 124.

- ^ Rebecca Dube, "Menorah Illuminates Davis Jr.'s Judaism", The Jewish Daily Forward, May 29, 2009.

- ^ Sammy Davis, Jr.'s 'Music, Money, Madness' – NPR.

- ^ "LegalZoom Will Upheld In Sammy Davis, Jr. Estate Battle". GlobeNewswire. May 6, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018.

- ^ "Sammy Davis, Jr. - Closest Of Friends". SammyDavisJr.Info. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Obituary: Elvera Davis, 95, Tap Dancer And Mother of Sammy Davis Jr". The New York Times. September 8, 2000. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "What Made Sammy Dance?". Time. October 23, 2003. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ a b Haygood, Wil (2003). In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis Junior. New York: A. A. Knopf (Random House). p. 516. ISBN 0-375-40354-X. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ Davis, Sammy Jr.; Boyar, Jane; Boyar, Burt (2000). Sammy: An Autobiography: with Material Newly Revised from Yes I Can and Why Me?. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-374-29355-0. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ "Rufus Jones for President", British Film Institute, (1933)

- ^ Santosuosso, Ernie (May 17, 1990). "Sammy Davis Jr., Entertainer for Six Decades, Dies at 64". The Boston Globe.

- ^ a b c "Davis, Samuel G., Jr., Pvt". Army.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Monod, David (2005). Settling scores: German Music, Denazification, & the Americans, 1945–1953. UNC Press. p. 57.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr". Oral Cancer Foundation. February 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Eagle, Bob L.; Leblanc, Eric (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. ABC-CLIO. p. 261. ISBN 9780313344244. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ E.g. Billboard, July 25, 1953, p. 11.

- ^ "Report Sammy Davis Signs $100,000 TV Pact". Jet. 3 (22): 59. April 9, 1953.

- ^ "Forecast: Sammy Davis In 3-D". Jet. Vol. 4, no. 12. July 30, 1953. p. 11.

- ^ a b Haygood, Wil (2003). In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. New York : A.A. Knopf : Distributed by Random House. pp. 148-149. ISBN 9780375403545.

- ^ Haygood, Wil (October 7, 2003). In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. A. A. Knopf. p. 156. ISBN 9780375403545. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Fishgall, Gary (September 30, 2003). Gonna Do Great Things: The Life of Sammy Davis Jr. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-7432-2741-4. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ "Jr. Davis Carves 'Turkey' Into B.O. Winner Vs. Critics". Variety. October 24, 1956. p. 1.

- ^ Guralnick, Peter. (2005). Dream boogie : the triumph of Sam Cooke (1st ed.). New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316377945. OCLC 57393650.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr will crown..." Photo caption Mirror News July 31, 1958.

- ^ Raymond, Emilie (2015). "Sammy Davis, Jr: Public Image and Politics". Cultural History. 4 (1): 42–63. doi:10.3366/cult.2015.0083.

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr., Burt Boyar, and Jane Boyar, Sammy: The Autobiography of Sammy Davis Jr. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000).

- ^ Parris, Amanda (April 25, 2018), CBC's digging up its music archives, and it couldn't have happened at a better time, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr. on Parade, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, November 15, 2018

- ^ Sinatra, Nancy (June 17, 2000). "Nancy Sinatra Reminisces". Larry King Live (Interview). Interviewed by Larry King. CNN. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ Chadbourne, Eugene. "Sammy Davis Jr. Now". AllMusic. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Sammy Jr. (June 22, 1973). "Advertisement thanking the participants". Daily News. New York. p. 55.

- ^ "The Highway Safety Foundation: A Chronology". Documenting reality. 1973. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Blavat, Jerry (August 13, 2013). You Only Rock Once: My Life in Music. Running Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-7624-5018-3.

- ^ "Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli and Sammy Davis Jr. Announce Concert Tour". AP NEWS. April 14, 1988.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (July 5, 1990). "Review/Television; With Sammy Davis, the Spirit Lingers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ a b "Sammy Davis Jr. Treated For Throat Malignancy". Jet: 54–55. September 25, 1990.

- ^ a b c d e Rosen, Marjorie (May 28, 1990). "The Entertainer". People.

- ^ a b "Sammy Davis Jr. Succumbs To Cancer". The Philadelphia Inquirer. May 17, 1990. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr's 1972 Presidential Mission to Vietnam". Recoveryteam.tv. July 8, 2016.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr. in Vietnam, 1972". Stars and Stripes. September 29, 2013.

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr. in Vietnam, 1972 Documentary on YouTube

- ^ Early, G. L. (2001). The Sammy Davis Jr. reader. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- ^ Flint, Peter B. (May 17, 1990). "Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64; Top Showman Broke Barriers". The New York Times.

- ^ Haygood, Will (September 13, 2003). "The Hug". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Davis supports Jackson". Minden Press-Herald. February 6, 1984. p. 1.

- ^ Cannon, Bob (November 20, 1992). "The Unflappable Sammy Davis Jr." Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ "Why JFK Refused to Let Sammy Davis Jr. Perform at White House". ABC News. April 18, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Price, Mark J. (November 25, 2012). "Local History: Akron Legend About Sammy Davis Jr. Turns Out to Be True". Akron Beacon Journal. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Davis, Sammy Jr.; Boyar, Jane & Burt (1990). Yes I Can: The Story of Sammy Davis, Jr. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52268-5.

- ^ "Nice Fellow". Time. April 18, 1955. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "Pamphlet from Birdland Jazz Club". 1955. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ What's My Line? – Sammy Davis, Jr (March 13, 1955) on YouTube

- ^ Green, David B. (May 16, 2013). "This Day in Jewish History 1990: Sammy Davis Jr., Famous Convert to Judaism, Dies". Haaretz. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Religion: Jewish Negro". Time. February 1, 1960. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ Weiss, Beth (March 19, 2003). "Sammy Davis, Jr". The Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ Sammy Davis Jr. Turns Near Tragedy into Triumph], San Bernardino Sun, September 28, 2008 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Lanzendorfer, Joy (August 9, 2017). "Hollywood Loved Sammy Davis Jr. Until He Dated a White Movie Star". Smithsonian. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Reid, Ed; Demaris, Ovid (1963). The Green Felt Jungle. Cutchogue, New York: Buccaneer Books. LCCN 63022217.

- ^ December 2014 BBC documentary, Sammy Davis, Jr. The Kid in the Middle.

- ^ "Loray White Davis Granted Divorce". Daily Press. Newport News, VA. Associated Press. April 24, 1959. Retrieved October 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nichols, Nichelle (1994). Beyond Uhura Star Trek and Other Memories.

- ^ Newport, Frank "In U.S., 87% Approve of Black-White Marriage, vs. 4% in 1958", Gallup News, July 25, 2013.

- ^ Loving v. Virginia.

- ^ "Tracey Davis, daughter of Sammy Davis Jr., dies age 59". Daily News. New York. November 18, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ "Sammy Davis Jr.'s daughter understood her father's commitment to Judaism". The Forward. November 20, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ "Author Tracey Davis, daughter of Sammy Davis Jr., dies at 59". Today.com. November 17, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Tracey Davis, Chronicler of Ups and Downs With Her Famous Father, Dies at 59". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 20, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Dagan, Carmel (December 8, 2015). "Sammy Davis Jr. Kept His Cool in a Less-Tolerant Era". Variety (magazine). Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Young, Deborah (September 10, 2017). "'Sammy Davis, Jr.: I've Gotta Be Me': Film Review | TIFF 2017". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ "Sammy Davis, Jr. Leaves An Estate Valued at $4 Million, Probate Court Petition Reveals". Jet: 4–5. August 27, 1990.

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Rich (November 2, 2008). "As Sammy's star imploded". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Davis, Sammy Jr. (July 1989). "Sammy Davis Jr. Faces Life, Aging and Cocaine". Ebony: 66, 68.

- ^ a b "Sammy Leaves Estate to Wife; Prized Gun to Clint Eastwood". Los Angeles Times. August 8, 1990. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ Boyar, Burt (2007). Photo by Sammy Davis, Jr. New York: Regan Books. p. 338. ISBN 9780061146053.

- ^ Hurst, Jack (August 26, 1994). "Johnny Cash's War Within". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Alex Bhattacharji (August 4, 2024). "Inside Sammy Davis Jr.'s Secret Satanic Past". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ Anka, Paul; Dalton, David (2013). My way. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-38104-2.

- ^ Andreassi, George (June 17, 1985). "Entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. said Monday his bout with..." United Press International.

- ^ a b Rochman, Sue (2007). "The Cancer That Silenced Mr. Wonderful's Song". CR. 2 (3). Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Simmonds, Yussuf (July 30, 2009). "Sammy Davis Jr". Los Angeles Sentinel. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ Folz, B. J.; Ferlito, A.; Weir, N.; Pratt, L. W.; Werner, J. A. (June 1, 2007). "A historical review of head and neck cancer in celebrities". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 121 (6): 511–20. doi:10.1017/S0022215106004208. ISSN 1748-5460. PMID 17078899. S2CID 22164447. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Flint, Peter B. (May 17, 1990). "Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64. Top Showman Broke Barriers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

Sammy Davis Jr., a versatile and dynamic singer, dancer and actor who overcame extraordinary obstacles to become a leading American countentertainer, died of throat cancer yesterday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 64 years old and had been in deteriorating health since his release from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center on March 13.

- ^ Clarke, Norm (May 17, 2015). "Anniversary of Sammy Davis Jr.'s death comes and goes in Las Vegas". Las Vegas Review Journal. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

Many consider Davis the greatest all-around entertainer. After he died on May 16, 1990, he received the ultimate Las Vegas tribute: the lights went dark on the Strip to honor the song-and-dance icon.

- ^ Tayman, John (October 7, 1991). "Sammy's Troubled Legacy". People. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ a b "Altovise Davis Struggles To Cope With Debt Left By Sammy Davis Jr". Jet: 54–56. October 28, 1991.

- ^ a b "Altovise Davis, Wife of Late Entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., Settles $7 Million Dispute With IRS Against Husband's Estate". Jet: 32. May 26, 1997.

- ^ Yoder, C. (June 2010). "Sammy Davis, Jr.'s Son Tests LegalZoom Last Will in Court". LegalZoom. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "SCTV Review: The Sammy Maudlin Show (1-21) / World at War (1-22)". July 8, 2021.

- ^ "SCTV Guide - Programs - the Sammy Maudlin Show".

- ^ SCTV @ YouTube

- ^ "Sammy and Company (1975)". The A.V. Club.

- ^ "Sammy Davis, Jr. - Sammy & Company, 1975-77". Sammydavisjr.info. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020.

- ^ "This week in TV Guide: July 9, 1966".

- ^ "CTVA US Music Variety - "Sammy and Company" (Syndicated)(1975-77) Sammy Davis, Jr".

- ^ Rival Rat Pack Reopens West End Whitehall, 18 Sep – News Archived June 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Whatsonstage.com. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ "HOME". I GOTTA BE ME.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick. "Sammy Davis Jr Biopic Aligns With Estate, Moves Foward [sic] With Producers Lionel Richie & Lorenzo Di Bonaventura". Deadline. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Grein, Paul (November 15, 1989). "Toasting a Song-and-Dance Man : Pop: An all-star cast salutes Sammy Davis Jr. on his 60th anniversary in show business with a heartfelt tribute to his role in breaking down barriers for black performers". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Sammy Davis, Jr.'s 60th Anniversary Celebration". Television Academy. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Las Vegas Walk of Stars" (PDF). Lasvegaswalkofstars.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- ^ "Cite Sammy". Jet: 61. November 16, 1961.

- ^ "Sammy Davis, Jr". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019.

- ^ "You Were There", a song by Michael Jackson and Buz Kohan, was performed by Michael Jackson during this show.

Further reading

[edit]Autobiographies

[edit]- Yes, I Can (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (1965), ISBN 0-374-52268-5

- Why Me? (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (1989), ISBN 0-446-36025-2

- Sammy (with Burt and Jane Boyar) (2000), ISBN 0-374-29355-4; consolidates the two previous books and includes additional material

- Hollywood in a Suitcase (1980), ISBN 0-425-05091-2

Biographies

[edit]- Haygood, Wil (2003). In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr. New York: A. A. Knopf (Random House). ISBN 0-375-40354-X.

- Birkbeck, Matt (2008), Deconstructing Sammy: Music, Money, Madness, and the Mob. Amistad. ISBN 978-0-06-145066-2

- Silber, Arthur Jr. (2003), "Sammy Davis Jr: Me and My Shadow, Samart Enterprises, ISBN 0-9655675-5-9

Other

[edit]- Photo by Sammy Davis, Jr. (Burt Boyar) (2007) ISBN 0-06-114605-6

- Susan King (May 10, 2014). "Classic Hollywood: Daughter's 'Personal Journey' with Sammy Davis Jr". Los Angeles Times.

- "Sammy Davis Jr. Drive in Langston, OK".

External links

[edit]- "Burt Boyar collection of Sammy Davis, Jr. biographical materials, 1954–2000". Music Division, Library of Congress.

- "Sammy Davis, Jr. arrangements 1953–1988". Music Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

- Sammy Davis Jr.'s Discography @ sammydavisjr.info

- Sammy Davis Jr. recordings at the Discography of American Historical Recordings

- "William Morris Agency Billing Contract for the Will Mastin Trio & Sammy Davis Jr". University of Nevada Las Vegas. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- Sammy Davis Jr. FBI Records: The Vault – at fbi.gov

- Sammy Davis Jr. at the Internet Broadway Database

- Sammy Davis Jr. at IMDb

- "Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64; Top Showman Broke Barriers", The New York Times, May 17, 1990.

- Davis Jr. talks to draft dodgers in Canada, CBC Archives

- Sammy Davis Jr. @ Archival Television Audio

- programme on Sammy Davis Jr. @ BBC Radio 4

- Photographic Image of Sammy Davis Jr. taking a photograph of his wife May Britt and newly adopted son Jeff on steps of Los Angeles County Courthouse, California, 1965. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Sammy Davis Jr.

- Sammy Davis Jr. albums

- 1925 births

- 1990 deaths

- 20th-century African-American male actors

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American memoirists

- 20th-century converts to Judaism

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- Activists from Manhattan

- African-American activists

- African-American comedians

- African-American film producers

- African-American jazz musicians

- African-American jazz pianists

- African-American Jews

- African-American male child actors

- African-American male comedians

- African-American male dancers

- African-American male singers

- African-American memoirists

- African-American television directors

- African-American television talk show hosts

- American actors with disabilities

- American entertainers of Cuban descent

- American impressionists (entertainers)

- American jazz singers

- American LaVeyan Satanists

- American male child actors

- American male comedians

- American male dancers

- American male film actors

- American male jazz pianists

- American male musical theatre actors

- American male soap opera actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American musicians of Cuban descent

- American musicians with disabilities

- American tap dancers

- American television directors

- American television talk show hosts

- American vaudeville performers

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- California Democrats

- Charly Records artists

- Comedians from California

- Comedians from Manhattan

- Converts to Judaism from Christianity

- Converts to new religious movements

- Converts to Reform Judaism

- Dancers from New York (state)

- Deaths from esophageal cancer in California

- Deaths from throat cancer in California

- Decca Records artists

- Eyepatch wearers

- Film producers from New York City

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Hispanic and Latino American male actors

- Hispanic and Latino American male comedians

- Hispanic and Latino American musicians

- Jazz musicians from California

- Jazz musicians from New York (state)

- Jewish American comedians

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish American musicians

- Jewish film people

- Jewish jazz musicians

- Jewish male comedians

- Jewish singers

- Jews from California

- Jews from New York (state)

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Las Vegas shows

- Male actors from Beverly Hills, California

- Male actors from Manhattan

- Military personnel from Manhattan

- Musicians from Beverly Hills, California

- People from Harlem

- People from South End, Boston

- Rat Pack

- Reprise Records artists

- Roulette Records artists

- Singers from California

- Singers from New York City

- Singers with disabilities

- Tobacco-related deaths

- Traditional pop music singers

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- United States Army soldiers